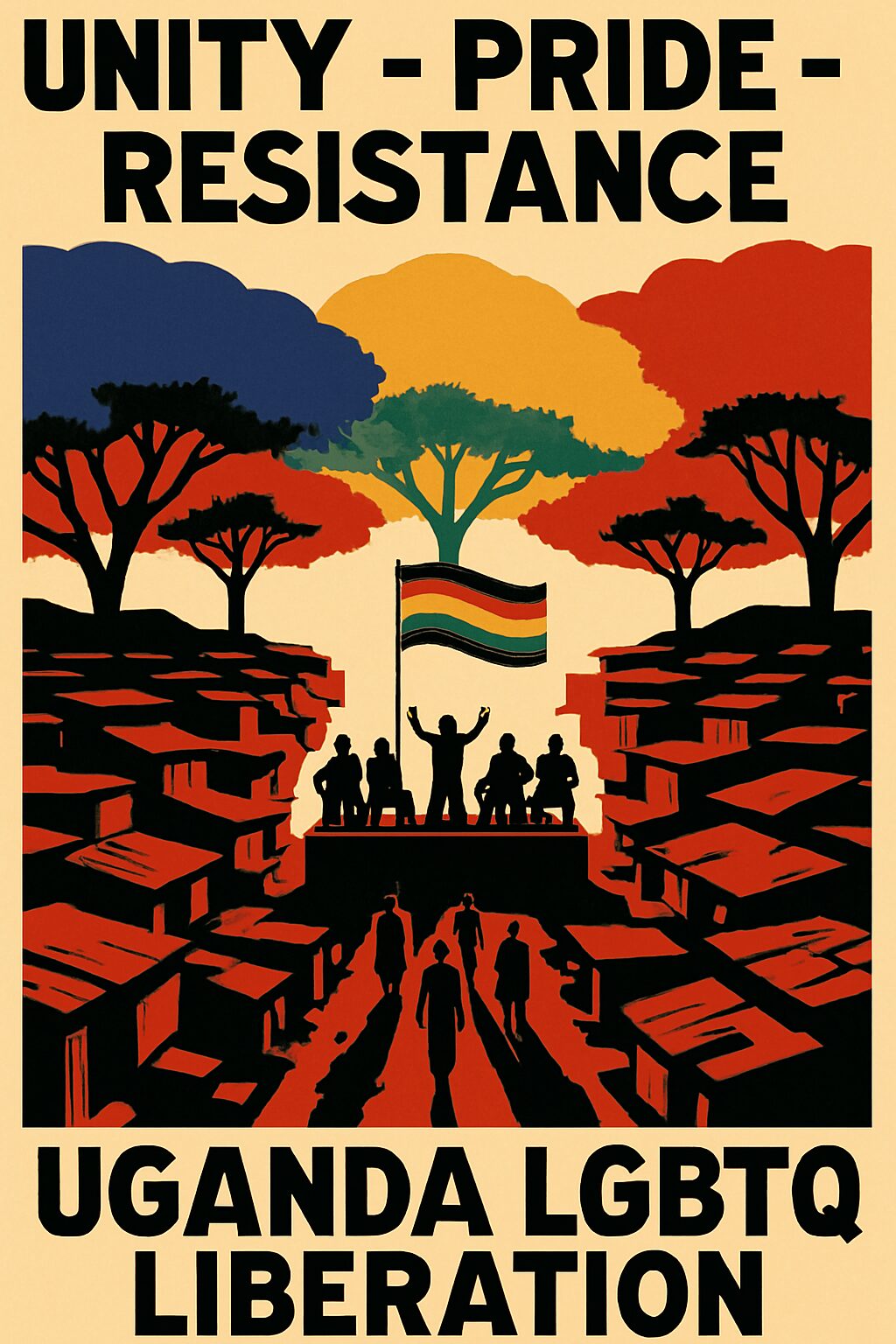

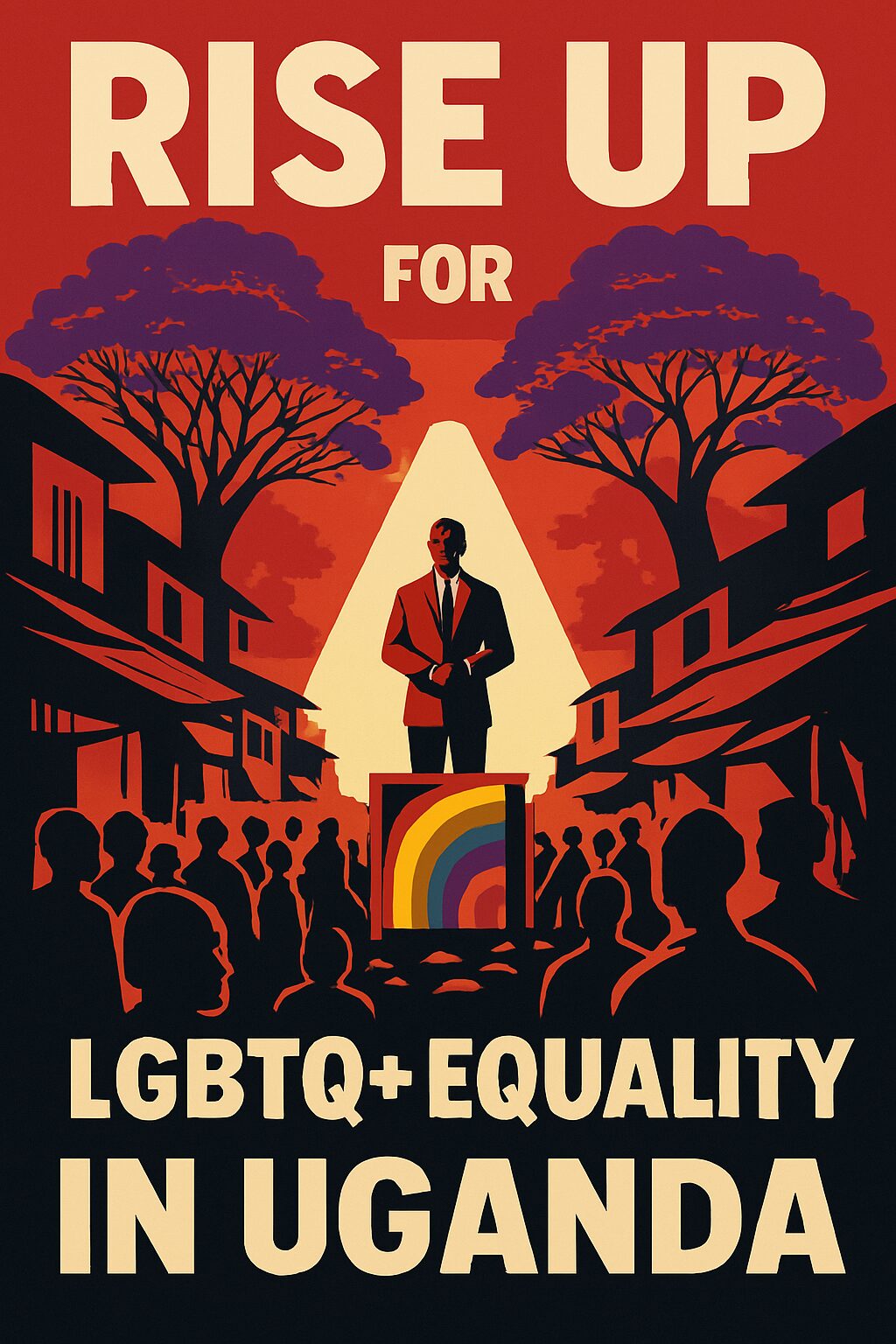

Uganda LGBTQ Resistance : Stories of Defiance, Faith, and Freedom

Uganda’s LGBTQ+ narrative is one of resilience, resistance, and rebirth. Against the backdrop of the controversial Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA), a powerful movement has emerged — blending faith, art, storytelling, and activism to challenge oppression and reclaim queer identity in East Africa. From the hidden corners of Kampala to the dusty archives of Entebbe, individuals like Pastor Ezekiel Kato, law student Tina Namutebi, and activist Annet Nakimuli are rewriting Uganda’s history by uncovering pre-colonial traditions that once embraced gender fluidity and same-sex love. Their stories — captured in oral histories, banned essays, underground poetry, and encrypted journalism — reveal a nation at a crossroads between tradition and transformation.

This exploration delves into the heart of queer life in Uganda, where digital activism meets divine love, and where progressive Christianity stands defiant against religious extremism. It uncovers how colonial-era laws such as Section 145 continue to shape modern-day persecution, while also highlighting the courage of those who dare to exist, love, and speak truth to power. From Nairobi to Gulu, from Kakuma Refugee Camp to the halls of Parliament, voices are rising — not just for freedom, but for remembrance, dignity, and justice.

Whether you’re seeking insight into African queerness, the impact of evangelical influence, or the role of art in social change, this comprehensive guide offers an in-depth look at Uganda’s ongoing struggle for LGBTQ+ rights. Discover how underground movements, safe spaces, and international solidarity are helping to turn whispers into revolutions — and how the past may yet light the way forward.

Explore the untold stories of Uganda’s queer community, their fight for human rights, and their journey toward liberation — one story, one voice, one fire at a time.

In the heart of Kampala, beneath the sprawling canopy of jacaranda trees that paint the city in shades of purple and gold, a quiet storm brews. It is not one of thunder or violence, but of conscience—of voices rising against a law that has become both a symbol of fear and a catalyst for resistance. Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA), passed in 2023, has drawn global condemnation and domestic division. But beyond headlines and diplomatic spats lies a deeper story—one of resilience, betrayal, faith, and hope.

The Purple Storm: A Nation at a Crossroads

“A bird may fly alone, but it finds strength in the flock.”

In the city of Kampala, where the jacaranda trees bloom like forgotten dreams and the air smells of rolex wraps and diesel fumes, there lives a quiet storm — not of thunder or lightning, but of conscience.

It begins beneath a tree.

Not just any tree — a jacaranda, its branches heavy with purple blossoms that fall like secrets onto the dusty ground below.

And under that tree, three people sit.

One is Annet Kansiime , once a lecturer, now a legend whispered in classrooms and coded messages. She has survived imprisonment, exile, silence. Her voice is softer now, but sharper.

Beside her is Kato Mwesigwa , a filmmaker whose camera sees what eyes are too afraid to look at. He hides behind lenses, but his truth is naked as the sky.

And beside him is Ocen , a young man who loves Kato more than he fears death.

They are not alone.

Around them, others gather — students, activists, elders, even a few curious children chasing petals in the wind.

They speak in hushed tones, knowing that words can be as dangerous as bullets.

Because this is Uganda.

And Uganda is at a crossroads.

Act I: The Law That Divided – When Fear Became Policy

The law had come down like a hammer.

Passed with fanfare and fireworks, blessed by pastors and politicians alike, the Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) was hailed by some as a victory for morality — and condemned by others as a crime against humanity.

To Dictator Yoweri Museveni, it was a symbol of sovereignty:

“We will not let Western perverts turn our children into sodomites.”

To the world, it was a violation of basic human rights.

But to those living under it?

It was something else entirely.

It was betrayal .

It was banishment .

It was prison sentences for love .

Annet had watched it unfold from her small flat above a tailor’s shop.

She remembered the first time she heard the news:

“Life imprisonment for ‘promoting homosexuality.’ Twenty years for being caught in same-sex relations.”

She laughed bitterly.

“As if love could be arrested.”

But many were.

Some vanished.

Others were beaten in the streets.

And still, others began to fight back.

Act II: The Lovers in the Shadows – When Love Was a Crime

Kato and Ocen met in secret — in basements, alleyways, and abandoned garages where no one listened except the rats and the rain.

Their love was tender. Quiet. Dangerous.

Once, they kissed behind the library at Makerere University.

Someone saw.

They were chased. Beaten. Separated.

Ocen spent two weeks in prison.

When he came out, he couldn’t sleep.

He would wake up screaming.

Kato held him close.

“We’re still here,” he whispered.

But sometimes, being alive felt like punishment enough.

Still, they stayed.

Because running meant losing each other.

And losing each other meant losing everything.

Act III: The Betrayal – When Friends Become Foes

Not everyone turned away.

Some stood firm.

Like Pastor Rev. Okello , once known for fiery sermons condemning queerness, now preaching compassion from the pulpit.

Or Tina Namutebi , a law student who risked expulsion to write essays defending queer Ugandans.

Even Inspector Mubiru , a police officer disillusioned by brutality, leaked classified documents exposing torture in prisons.

But betrayal also came from unexpected places.

A friend. A cousin. A lover.

Someone always sold someone out.

Sometimes for money.

Sometimes for safety.

Sometimes because they believed the lies.

There was a saying among activists:

“Trust only the ones who’ve bled with you.”

And in Uganda, blood ran deep.

Act IV: The Resistance Rises – When Silence Turns Into Song

Then came the whispers.

First in cafés. Then in WhatsApp groups. Then in poems scribbled on toilet paper and passed through prison bars.

Artists painted murals of lovers beneath baobab trees.

Students staged plays about ancient African traditions that embraced diversity.

Journalists wrote stories disguised as fiction.

And underground radio stations played songs banned from state airwaves.

One such song went viral:

“I Am Not a Sin”

“My heart beats for him,

Not because of pride,

But because of love.

And love does not ask permission.”

People wept.

Others raged.

But all listened.

Because this was no longer just about laws.

It was about identity.

About dignity.

About reclaiming a future stolen by fear.

Epilogue: The Choice – At the Edge of Tomorrow

Back beneath the jacaranda tree, Annet looks at Kato and Ocen.

She speaks softly.

“You know, this country is at a crossroads.”

Kato nods.

“One path leads back to fear. The other… to freedom.”

Ocen adds:

“But which way do we go?”

Annet smiles faintly.

“That’s not for us to decide. It’s for the next generation.”

Above them, the jacaranda blooms.

Its petals fall like memories.

Like choices.

Like futures waiting to be made.

And somewhere in the distance, a child laughs.

Unaware of the battles fought on their behalf.

But not unaware of the hope.

This is a brutal, beautiful story — of fear and faith , of betrayal and bravery , of silence and song .

It reminds us that no nation is born divided — it becomes so through choice .

And as the old adage says:

“A bird may fly alone, but it finds strength in the flock.”

Let Uganda choose its flock wisely.

Let it remember its past.

Let it dream its future.

Let it walk toward the light — not away from it.

Because the crossroads is not a place to stay.

It is a place to choose.

And the choice?

Belongs to the people.

1.The Ghost That Wears a Crown: How a Law Was Born in Shadows

“A bird that flies off the Earth and lands on an anthill is still on the ground.”

In the dusty archives of Entebbe Palace, where the air smells of old paper and forgotten promises, a young law student named Tina Namutebi flipped through yellowed documents, her fingers trembling as if touching ghosts.

She had come searching for truth.

What she found was betrayal.

Buried beneath colonial reports and post-independence decrees were laws written in cold ink by men who never walked these streets — British administrators who mapped out morality like borders, carving crime into love, and sin into identity.

They called it:

“Section 145: Carnal Knowledge Against the Order of Nature.”

Tina read it aloud to herself, tasting the bitterness of words that had outlived their makers.

And yet, they still ruled.

Act I: The Shadow of Empire – When Foreign Devils Left Local Demons Behind

Back in Kampala, Elder Ntawula , once a respected historian and now a forgotten voice in a world that no longer listened, sat beneath the jacaranda tree outside his village church.

He told stories — not the kind you hear on radio or read in schoolbooks, but the kind passed down like heirlooms.

One evening, he spoke to a group of curious students about what life was like before the missionaries came.

“We had many names for love,” he said. “Some of them didn’t fit inside one body.”

A girl raised her hand.

“So… homosexuality is African?”

The elder smiled sadly.

“It always was. But when the white man came, he brought two things: a Bible and a law. And he made us choose between them.”

Then came the missionaries — not just from London and Rome, but from Texas and Tennessee.

They built churches with steel and sermons soaked in fire.

One such preacher, Pastor Elijah Mwesigye , rose to fame after returning from a revival conference in Dallas.

He stood before a crowd in Masaka and declared:

“God did not make Adam and Steve! He made Adam and Eve — and anyone who says otherwise is cursed!”

The crowd cheered.

But somewhere in the back, a woman whispered to her daughter:

“Your uncle used to love men. They called him ‘the Lioness of Kitara.’ Everyone respected him.”

Her daughter shushed her.

“Don’t speak like that. You’ll get us killed.”

Act II: The Holy War – When Faith Became Fire

Fast forward to 2023.

Kampala was buzzing with anticipation.

President Yoweri Museveni , flanked by bishops and foreign preachers, stood at the podium in State House, holding a thick red bill like a sword.

Behind him, a banner read:

“UGANDA STANDS TALL: NO FOREIGN PERVERSION!”

He began:

“We are not afraid of Western threats. We will not let sodomites ruin our children. This is Africa. This is Uganda. And we will not be dictated to!”

The crowd roared.

Across town, Annet Kansiime watched from her balcony, sipping tea with trembling hands.

She remembered her father telling her:

“Colonialism didn’t end — it just changed clothes.”

Now, it wore a cassock.

Now, it carried a Bible.

Now, it signed death sentences with a cross.

Act III: The Betrayal of the People – When Leaders Stole Love to Sell Fear

Meanwhile, in a dimly lit room above a bar in Kololo, a meeting took place among politicians, religious leaders, and media moguls.

The topic?

Not poverty.

Not corruption.

Not unemployment.

But homosexuality .

A minister leaned forward.

“If we pass this law, the churches will rally behind us. The donors can shout all they want — they won’t stop the people.”

Another nodded.

“And if we distract the youth with hate, they won’t notice how little we’ve done for them.”

A journalist added:

“We’ll call it sovereignty. Call it tradition. Call it God’s will.”

They laughed.

Because they knew.

Laws weren’t made to protect.

They were made to control.

Act IV: The Crime Called Compassion – When Love Was Made Illegal

Weeks later, the law was passed.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) .

It was brutal.

Life imprisonment for “aggravated homosexuality” — which included being HIV-positive and queer.

Twenty years for “promotion” — meaning writing, speaking, or even thinking differently.

And ten years for failing to report a known homosexual.

Suddenly, neighbours became spies.

Parents feared their own children.

Doctors refused to treat patients.

Even Inspector Mubiru , a veteran officer known for his honesty, was ordered to raid a safe house where queer youth gathered to share poetry and dreams.

He hesitated.

Then he entered — not with handcuffs, but with tears.

He arrested no one.

Instead, he warned them.

“Run. Hide. Don’t trust anyone.”

That night, he handed in his badge.

And vanished.

Act V: The Bird Still Flies – When Hope Refused to Die

Beneath the jacaranda tree, Annet met with Kato , a filmmaker whose camera had captured the quiet rebellion of queer Ugandans.

He showed her a clip.

A boy reading a poem titled:

“I Am Not a Sin”

Beside him, a girl recited lines from Annet’s banned essays.

“To be queer in Uganda is not a crime. It is a courage.”

Annet wiped away a tear.

“They think silence will kill us. But silence only feeds the fire.”

Kato smiled.

“Let them write their laws. We’ll write our stories.”

And across the country, stories began to bloom.

In hidden corners of schools, students debated whether queerness was truly un-African.

On underground radio stations, voices sang songs of love and defiance.

And in villages far from Kampala, elders began whispering tales of the balyeki — men who lived as women and served as spiritual guides.

The past was waking up.

And it was angry.

Epilogue: The Anthill Still Rises – When Freedom Fights Back

Years later, the AHA remained on the books.

But so did resistance.

Activists smuggled evidence out of prisons.

Lawyers challenged the law in court.

Artists painted murals of lovers beneath baobab trees.

And in the hills of Luweero, where mango trees bore witness to history, a new proverb emerged:

“A bird that flies off the Earth and lands on an anthill is still on the ground.”

But someone whispered back:

“Only until it learns to fly higher.”

And so, the fight continued.

Not because victory was near.

But because surrender was worse.

2. The Serpent in the Sanctuary: A Tale of Faith, Fear, and Foreign Fire

“Maji ya moto hayoogei.”

“Hot water cannot remain hot forever.”

In the hills of Luweero, where the wind carries secrets and old men still remember the war, there lived a preacher named Pastor Ezekiel Kato — once known as “the Voice of Righteous Fire.”

He had started small, preaching to a congregation of thirty in a mud-walled church behind a maize field.

But then came the Americans.

They arrived not with guns, but with Bibles wrapped in plastic and promises stitched into sermons.

They called themselves “The Light Bearers” — a Texas-based evangelical group claiming to fight moral decay across Africa.

To Pastor Kato, they were saviours.

To others?

They were snakes in the sanctuary.

Act I: The Gospel of Hate – When Love Was Called Sin

It began with a conference.

Not in Washington or Dallas — but in Kampala.

At the Kampala International Conference Centre , under banners reading:

“African Values, Christian Truths, Global Purity”

Evangelists from America spoke with fire in their voices and funding in their pockets.

One speaker, a man named Reverend Paul Jenkins , stood before a crowd of bishops, MPs, and media moguls.

“Africa,” he declared, “is under siege! Homosexuality is infiltrating your schools, your churches, even your families. But Uganda — Uganda can lead the way!”

The crowd erupted.

Pastor Kato was among them — eyes wide, heart pounding.

That night, he returned home changed.

He rewrote his sermons.

He burned his old hymnals.

And when Sunday came, he stood before his flock and roared:

“Homosexuality is not African! It is a Western plague sent by Satan himself!”

Children clutched their parents.

Old women crossed themselves.

And somewhere in the back row, a boy named Joseph held his boyfriend’s hand tighter beneath his coat.

Act II: The Marriage of Power and Piety – When Politics Wore a Cassock

Weeks later, President Yoweri Museveni hosted a private dinner at State House.

Guests included:

- The Speaker of Parliament.

- A bishop from Gulu.

- And Reverend Jenkins, now a frequent visitor to Uganda.

Over roast goat and imported wine, the president raised his glass.

“Let us protect our children. Let us defend our traditions. Let us be proud Africans — not sodomites.”

Jenkins nodded solemnly.

“We’ll help you write the law.”

And so they did.

Drafted in secret, leaked only to trusted allies, came the Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) — a document that criminalised love, punished silence, and turned neighbours into spies.

It passed like wildfire.

Some called it divine justice.

Others whispered of collusion .

Behind closed doors, emails revealed the truth.

One read:

“We’ve positioned Pastor Kato perfectly. He’s our mouthpiece.”

Another:

“Make sure the bill passes. Our donors are watching.”

And one final message, chilling in its simplicity:

“Let Uganda be our model. Then we move to Kenya.”

Act III: The Snake That Bit Twice – When God Became a Weapon

Pastor Kato became a national icon.

His face appeared on billboards:

“Stand Against Sodom!”

His radio show, “Truth Without Compromise,” filled the airwaves with venom.

“If Jesus walked among us today, he’d carry a whip—not a cross.”

At one rally, he led a chant:

“No mercy for perverts! No peace for sodomites!”

The crowd cheered.

But not everyone believed.

Among those listening was Annet Nakimuli , a journalist who had once been close to Kato — before she uncovered what he had become.

She found an old recording of him, from ten years ago.

Back then, he had said:

“God loves all sinners. Even those we don’t understand.”

Now, he preached hate dressed in holiness.

Annet knew something had changed.

And she wanted to know why.

Act IV: The Leak Heard ‘Round the Country

It started with a USB stick.

Left behind in a hotel room. Found by a maid who didn’t trust preachers.

Inside: encrypted files. Audio recordings. Video footage.

Secret meetings between American evangelicals and Ugandan lawmakers.

Plans to export anti-LGBTQ+ policies across East Africa.

Annet published everything.

Her article made headlines:

“The Serpent in the Sanctuary: How Foreign Preachers Helped Write Uganda’s Death Sentence.”

The world reacted.

Donors froze aid.

Diplomats condemned the collusion.

But within Uganda, the backlash was brutal.

Annet was arrested.

Charged with “spreading false propaganda.”

Her trial was televised.

Prosecutors accused her of “defaming religious leaders.”

Supporters watched in horror.

Then came the moment no one expected.

Pastor Kato took the stand.

He looked at Annet.

And for the first time, he hesitated.

Then he whispered:

“I was afraid.”

Silence.

“I was offered money. Protection. Influence. And I accepted.”

Gasps.

“But I never meant to destroy lives. I just wanted to be heard.”

Tears streamed down his face.

“Forgive me.”

He collapsed mid-testimony.

Taken away in an ambulance.

Later, he disappeared.

Some say he fled to Rwanda.

Others claim he died in exile.

But his words remained.

And they sparked something deeper than fear.

They sparked doubt.

Act V: The Fire Begins to Cool – When the People Begin to Question

In the weeks that followed, cracks formed.

Students staged sit-ins demanding dialogue, not dogma.

A bishop in Mbale released a pastoral letter:

“We have used God to justify cruelty. We must repent.”

Even members of parliament began to question whether the law served the people — or just the powerful.

On social media, hashtags trended:

- #ForeignFire

- #QueerAndProudUG

- #FaithWithoutFear

And in hidden corners of Kampala, a new movement rose — not of politics, but of people .

Artists painted murals of same-sex lovers beneath baobab trees.

Writers revived ancient proverbs about gender-fluid spiritualists.

And in schools, teachers dared to ask:

“Was homosexuality truly un-African?”

Joseph, the boy who once held his lover’s hand in church, now ran an underground safe house called:

“The Chapel Without Walls.”

There, no one was damned.

Only loved.

Only seen.

Only saved.

Epilogue: The Water Begins to Cool – When Truth Begins to Heal

Years later, the Anti-Homosexuality Act still stood.

But so did resistance.

Pastor Kato’s name faded into legend — remembered not as a hero, but as a warning.

The Americans left quietly, their influence slipping like sand through fingers.

President Museveni grew older.

So did Uganda.

And slowly, steadily, the people began to speak again.

Of love.

Of history.

Of healing.

As the Swahili saying goes:

“Pata mbwa mwenye meno mabaya, usimtazame kama mkulima wa nyama.”

“When you see a dog with bad teeth, don’t mistake him for a butcher.”

And so, Uganda learned to see clearly.

That faith should heal — not harm.

That religion should unite — not divide.

And that some prophets were merely puppets.

Pulling strings from afar.

3. The Ink That Burned a Law: A Tale of Whispers, Cameras, and Courage

“Omukama atebe omugezi.”

“A king does not eat alone.”

In the back room of a crumbling building behind Nakaseke Market, where the air smelled of fried cassava and fear, Kato adjusted the lens of his camera like a surgeon preparing for surgery.

His hands trembled—not from nerves, but from purpose.

On the screen before him were images that could get him killed.

A video clip of Pastor Ezekiel Kato preaching hate in Masaka.

A scanned document titled:

“Strategic Messaging Framework: Framing Homosexuality as Western Disease.”

And most damning of all — a series of emails between Ugandan lawmakers and American evangelical leaders.

One read simply:

“Make sure the bill passes. Our donors are watching.”

Kato clicked “save.”

Then he whispered:

“Let them come.”

Because he knew what this meant.

He had just lit a match in a house built of lies.

Act I: The Whisper That Roared – When Truth Was Not Silent Anymore

Back in Kampala, Annet Nakimuli sat at her desk in the newsroom of The Daily Flame , Uganda’s last semi-independent newspaper.

She was forty-two, sharp-tongued, and tired of pretending.

Her latest article—titled:

“The Sinister Calculus: Who Really Wrote the Anti-Homosexuality Act?”

—was ready for print.

It was more than an exposé.

It was a reckoning.

She detailed how foreign evangelicals had trained local politicians in messaging techniques borrowed from American culture wars.

How churches had become campaign offices.

How laws were written not by lawmakers, but by lobbyists hiding behind crosses.

She ended with a line she knew would haunt her:

“They told us homosexuality was un-African. But they forgot to mention that hatred came in a suitcase.”

Hours later, her editor called.

“You’re going to get us shut down.”

She replied:

“Better a dead paper than a silent one.”

Act II: The Cat Is Away – When Lions Took the Stage

The world reacted faster than Uganda expected.

Within days, headlines across Europe and America screamed:

“Uganda’s Morality Playbook Was Written in Texas.”

Foreign embassies summoned diplomats.

Donors froze aid.

Visa bans were issued against MPs who had signed off on the law.

President Museveni raged.

“We do not take orders from sodomite-loving foreigners!”

But inside Uganda, something deeper began to stir.

Students gathered outside Makerere University chanting:

“Who wrote the law? Tell us the truth!”

Farmers in Mbale debated whether homosexuality was truly foreign or if they’d been sold a lie.

And in the streets of Kisenyi, graffiti appeared overnight:

“The Serpent Wears a Cassock.”

“Truth Has No Visa.”

Even state TV anchors hesitated before reading scripted lines about “Western perversions.”

Some whispered instead:

“I’ve seen the emails.”

Act III: The Arrest – When Silence Tried to Swallow the Voice

One morning, dawn broke quietly.

Too quietly.

Annet woke to the sound of boots on stairs.

She barely had time to hide her notes before the door burst open.

Inspector Mubiru stood there — stone-faced, uniform pressed, eyes unreadable.

Behind him, two officers carried bags.

“Annet Nakimuli,” he said. “You are under arrest for spreading false propaganda and undermining national security.”

She didn’t resist.

Instead, she smiled.

“You already know the truth. You just haven’t decided which side you’re on.”

Mubiru looked away.

As they led her out into the pale light of morning, neighbours watched from behind curtains.

No one clapped.

No one cheered.

But many remembered.

And remembering is the first step toward rebellion.

Act IV: The Underground Press – When Journalism Went Rogue

With Annet gone, Kato took over.

He moved the operation underground — literally.

Newsletters printed on rice paper. Articles shared through WhatsApp voice notes. Videos uploaded via burner phones and smuggled out in shoe soles.

He gave himself a new name:

“The Whisperer”

His reports spread like wildfire.

One piece, titled:

“How God Became a Weapon”

Went viral.

It exposed how American preachers had paid Ugandan bishops to preach hate sermons.

Another, titled:

“The Seminar That Built a Prison”

Detailed how lawmakers had attended anti-LGBTQ+ training camps in Dallas disguised as “family values conferences.”

And then came the most daring act of all.

A leaked video of a secret meeting between President Museveni and Reverend Jenkins.

Jenkins leaned forward and said:

“We’ll make it look like Africa wants this. Then no one can stop us.”

The footage went global.

And Uganda burned.

Not with fire.

But with questions.

Act V: The Mouse That Roared – When the People Began to Speak

Across the country, ordinary citizens started speaking up.

A taxi driver in Jinja posted a TikTok video asking:

“Why are we arresting love but letting corruption walk free?”

A teacher in Gulu held class on pre-colonial African societies that accepted same-sex relationships.

A nurse in Mbarara filmed herself treating a queer patient and said:

“I don’t care what the law says. This person deserves care.”

Social media exploded.

Hashtags trended:

- #ExposeTheTruth

- #StopSilencingOurVoices

- #WhoReallyWroteTheLaw

Even within church walls, whispers grew louder.

A young seminarian stood during service and asked:

“If Jesus healed sinners, why do we punish the sick?”

The priest silenced him.

But others nodded.

And that silence?

Was louder than any sermon.

Act VI: The King’s Table – When Power Felt the Heat

Inside State House, panic brewed.

President Museveni slammed his fist on the table.

“These journalists think they are heroes. They are traitors.”

His press secretary tried to reassure him.

“They’re being arrested. Their networks are breaking.”

Museveni growled.

“They’re ghosts now. Ghosts whisper louder.”

Indeed, Kato had vanished.

But his work hadn’t.

From exile in Nairobi, he released a final report — a digital dossier filled with evidence, testimonies, and timelines.

Titled:

“The Serpent’s Manuscript: How Foreign Zealots Helped Criminalise Love.”

It made the rounds.

In Geneva. In Brussels. In Pretoria.

And even in the halls of Parliament, some MPs began to question their own votes.

One whispered:

“We were lied to.”

Another muttered:

“What if we passed a crime in the name of morality?”

Act VII: The Fire Still Burns – When Truth Refused to Die

Years passed.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act still stood.

But so did the people.

Annet was released after months in Luzira Maximum Security Prison — thinner, older, but sharper than ever.

She returned to writing.

Her first article back was titled:

“The Pen, the Pulpit, and the Politician: A Tragedy in Three Acts.”

Kato returned home under a new identity.

He founded a network of independent journalists called:

“The Hidden Quill”

Together, they kept telling stories.

About lovers forced into hiding.

About children disowned for loving differently.

About elders who remembered when gender wasn’t a cage.

And slowly, steadily, the tide turned.

Epilogue: The Tree Was Once a Seed – When One Voice Became a Forest

Under the jacaranda tree where everything had begun, a new generation gathered.

Young. Bold. Unafraid.

They read Annet’s old articles aloud.

They played Kato’s videos on cracked phone screens.

And they whispered:

“Truth may be fragile. But it never dies.”

As the sun dipped below the hills of Luweero, casting shadows long enough to touch history, a single phrase echoed among them:

“Omukama atebe omugezi.”

“A king does not eat alone.”

And neither does truth.

It feeds the people.

It builds the future.

It breaks the silence.

4. The Firewood That Waited for Flame: A Tale of Love, Loss, and Liberation

“N’omugenyi gwe mulwadde, tewali kwegatta nnyo.”

“In the home of your sister-in-law, there is no comfortable sleeping.”

In the narrow alleys of Nakaseke, where chickens peck at secrets and children play barefoot in dust, lived a boy named Joseph — though he sometimes called himself “Joshua” when he needed to disappear.

He was twenty-four, soft-spoken, and deeply in love.

His crime?

Loving another man.

Not in secret. Not in shame.

But openly — until the law made that impossible.

Now, Joseph slept with one eye open and a bag packed by the door.

Because in Uganda, love could be a death sentence .

Act I: The Knock at Dawn – When Love Became a Crime

It started with a knock.

Three sharp raps against the wooden frame of his aunt’s house in Masaka.

Joseph had just finished reading a poem Kato Namugga had written:

“We are not shadows,

Though they try to paint us so.

We are stars—hidden by day,

But burning still.”

Then came the voices.

“Open up! Police!”

Joseph didn’t move.

His cousin did.

Betrayed by family. Arrested by state.

They dragged him into the street.

Neighbors watched. Some looked away. Others smiled.

One whispered:

“They warned us this would happen.”

Joseph said nothing.

He knew better than to plead.

Because in Uganda, justice was only for those who obeyed .

Act II: The Cell That Whispered Lies – Where Humanity Was Stolen

Inside Luzira Maximum Security Prison, the air was thick with sweat, fear, and despair.

Joseph shared a cell with thieves, killers, and men like him — some broken, others still dreaming.

At night, they whispered.

“Did you hear about Sarah?” one asked. “She was sent back from Nairobi. Now she’s missing.” “And Kato? They say he fled to Kenya. Or maybe London.” “Or maybe he’s dead.”

Joseph closed his eyes.

He remembered his lover, Omondi , who had kissed him goodbye the morning before everything changed.

“Stay safe,” Omondi had whispered. “No matter what happens.”

Now, Joseph wondered if Omondi was alive.

Or if he, too, had been swallowed by the silence.

Act III: The Exile That Wasn’t Freedom – When Home Was No Longer Safe

Weeks later, Joseph was released — not because he was innocent, but because someone paid the right bribe.

He returned to Masaka.

But it wasn’t home anymore.

His mother wept when she saw him.

“You’ve brought shame,” she said quietly. “I can’t protect you anymore.”

That night, he packed his few belongings.

He left without saying goodbye.

He walked through banana plantations, past mango trees heavy with fruit, toward the border with Kenya.

By the time he reached Kakuma Refugee Camp , he had lost more than weight.

He had lost dignity.

But not hope.

There, among displaced souls and forgotten dreams, Joseph found others like him.

A Nigerian poet who wrote verses in Yoruba and English.

A Tanzanian woman who had survived corrective rape and now ran a shelter for queer women.

And a South Sudanese teenager who sang songs of survival beneath the stars.

Together, they formed a new family.

Built on scars.

Bound by fire.

Act IV: The Ink That Bled – When Words Were Weapons

Back in Kampala, Kato Namugga sat in a hidden room above a tailor’s shop in Kisenyi, typing furiously on an old laptop.

She had once dreamed of becoming a teacher.

Now, she was a soldier in the war for truth.

Her latest poem, titled:

“We Are Stars”

was already circulating across WhatsApp groups and encrypted chats.

She read it aloud to herself:

“They call us sinners,

Call us strangers,

Call us sickness in human skin.

But we are not shadows —

We are stars.

Hidden by day,

But burning still.”

Outside, the city buzzed with life.

Inside, Kato feared for her safety.

She knew the police were watching.

She knew her name was on a list.

But still, she wrote.

Because silence was the first step toward surrender.

Act V: The Song That Defied Silence – When Art Spoke Louder Than Law

In a disused mechanic’s garage in Ntinda, a group of young people gathered.

They called themselves “The Whisperers.”

They met every Friday.

Some brought poems.

Others brought music.

One girl danced like wind.

Another played guitar like rain.

And in the corner, a boy painted murals on the walls — portraits of same-sex lovers beneath baobab trees, of families built not by blood but by choice.

Their leader, Tina Namutebi , once a law student, now a fugitive, stood before them.

“They want us erased,” she said. “So we must become unforgettable.”

She opened a worn notebook.

“Let me tell you a story,” she began. “Of a boy who loved another boy. Of a nation that tried to kill them. And of how love survived.”

The room listened.

And somewhere, deep inside each of them, something stirred.

Courage.

Hope.

Resistance.

Act VI: The Invisible Wounds – When the Mind Hurts More Than the Body

But not all wounds bled.

Some festered inside.

Like Annet Kansiime , once a lecturer, now a ghost of her former self, sat alone in her flat in Kololo, staring at the wall.

She had survived prison.

She had survived exile.

But she had not survived the silence.

Each night, she dreamt of the students she used to teach.

Of the essays she used to write.

Of the daughter she had never held.

She began seeing things.

Hearing voices.

Feeling pain that had no source.

One evening, she visited a small underground clinic run by Dr. Namutebi , a retired psychologist who had turned her home into a sanctuary for the broken.

She sat across from him.

“I don’t know if I want to live anymore,” she confessed.

Dr. Namutebi placed a hand on hers.

“You are not weak,” he said. “You are wounded. But wounds can heal.”

He gave her a journal.

“Write your story. Let it bleed onto paper.”

And so she did.

Page after page.

Poem after poem.

Until healing became possible.

Act VII: The Firewood Waits – When the Flame Is Not Yet Lit

Years passed.

Joseph remained in Kakuma, working as a translator for aid agencies and writing letters to friends back home.

Kato vanished into the underground art scene, painting murals that appeared overnight — then disappeared before dawn.

Tina kept whispering truth into microphones smuggled into refugee camps.

Annet published her memoir anonymously online — and it went viral.

The world read her words.

And some Ugandans began to question.

Was homosexuality un-African?

Or had they simply been lied to?

As the Yoruba proverb says:

“Ẹni tí ń fọwọ́ sí ẹ̀rù ló pàṣẹ̀ fun ọ̀fẹ́.”

“He who carries the burden also gives orders.”

And slowly, the burden-bearers began to speak.

To sing.

To paint.

To protest.

To remember.

Epilogue: The Flame Will Come – When Firewood Meets Wind

Under the jacaranda tree in front of Makerere University, a new generation gathered.

They were younger.

Bolder.

Unafraid.

One of them held a copy of Annet’s book.

Another wore a T-shirt printed with Kato’s mural.

A third recited Tina’s poetry like scripture.

And someone whispered:

“The firewood waits. One day, the flame will come.”

Because resistance does not always roar.

Sometimes, it hums.

Sometimes, it hides.

Sometimes, it sleeps.

But never dies.

As the Luganda saying reminds us:

“N’omugenyi gwe mulwadde, tewali kwegatta nnyo.”

“In the home of your sister-in-law, there is no comfortable sleeping.”

But even in discomfort, there is defiance.

Even in exile, there is memory.

Even in fear, there is fire.

And someday, somehow, the match will strike.

The wood will burn.

And the darkness?

Will flee.

5. The Sermon That Bled: A Tale of Fire, Fear, and Faith

“Moyo mmoja hauwezi kushika maji”

“One heart cannot hold both water and fire.”

In the town of Gulu, where the sun beat down like a drum and the air smelled of roasted groundnuts and old regrets, there lived a man known to many as Pastor Ezekiel Kato — “The Voice of Fire.”

His sermons were broadcast across Uganda’s radio waves like thunder before a storm. His voice was deep, his words sharp, and his message clear:

“Homosexuality is not just sin. It is treason against God!”

Every Sunday, thousands gathered beneath the canvas tents of his megachurch, New Light Revival Centre , where miracles were promised and demons exorcised with mic-in-hand authority.

But behind the pulpit, behind the Bible raised high like a sword, lay something darker than faith.

Something crueler than belief.

Something closer to control .

Act I: The Sword in the Scripture – When Love Was Called War

Pastor Kato had not always been this way.

Once, he was simply Ezekiel Omondi , a humble preacher in a dusty village near Arua, teaching about grace, mercy, and the Good Samaritan.

But then came the Americans.

They arrived under the banner of “Global Evangelism Outreach” — a Texas-based group offering training, funding, and influence to local pastors willing to adopt their moral crusade.

Kato attended one seminar.

Then another.

And by the time he returned, he was no longer Ezekiel.

He was Pastor Fire .

He rewrote his sermons.

Burned his old hymnals.

And declared war on love.

At one rally, he stood atop a wooden stage draped in red cloth and shouted:

“God did not create man to lie with man! If we allow this abomination, He will strike our land with fire!”

The crowd roared.

Children clutched their parents.

A boy named Joseph , sitting in the back row, held his boyfriend’s hand tighter beneath his coat.

Act II: The Deliverance Ministry – Where Souls Were Torn Apart

Under Pastor Kato’s guidance, the New Light Church opened what they called the Divine Restoration Programme — a spiritual “healing camp” for those suffering from what he described as “the homosexual curse.”

It sounded noble.

It was anything but.

Inside a locked compound on the outskirts of Kampala, young men and women were subjected to days of fasting, prayer, and physical humiliation. Some were brought by families desperate to “save” them. Others were dropped off by well-meaning friends who believed the lies.

One such victim was Nakato , a seventeen-year-old girl who had kissed her best friend during a school trip and found herself branded a sinner.

She was taken to the compound in the dead of night.

There, she was told:

“You are possessed. You must be cleansed.”

For three days, she fasted.

On the fourth, she was made to stand before a congregation and confess:

“I am broken. I am unclean.”

She said it.

Because survival meant silence.

When she finally escaped, she carried more than scars.

She carried shame.

And rage.

Act III: The King’s Blessing – When Politics Wore a Cassock

Back in State House, President Museveni watched Pastor Kato’s rise with interest.

His approval ratings were slipping.

Corruption scandals brewed.

Unemployment soared.

But then came the sermons.

The rallies.

The national fervour.

Museveni saw opportunity.

He invited Kato to speak at a private event.

Behind closed doors, they shared goat stew and ambition.

Kato leaned forward.

“If you sign the Anti-Homosexuality Act, you’ll have the church behind you. No one can touch you.”

Museveni smiled.

“Then let us make history.”

And so they did.

Together, they forged a law that criminalised love, silenced dissenters, and gave preachers power over people’s lives.

Pastors became informants.

Churches became prisons.

And faith?

Faith became a weapon.

Act IV: The Heretic’s Whisper – When Doubt Dared to Speak

Not all clergy agreed.

In Jinja, Father Dominic , a soft-spoken Catholic priest with eyes that had seen too much, began questioning the narrative.

During Mass, he once said:

“Jesus ate with sinners, touched lepers, and forgave prostitutes. If He walked among us today, would He cast stones—or offer compassion?”

Silence followed.

Then murmurs.

Then threats.

Days later, someone threw a stone through his window.

Written on it in charcoal:

“Stop defending demons.”

Dominic didn’t stop.

Instead, he started holding secret meetings in the basement of his parish.

There, queer youth found sanctuary.

There, survivors found solace.

And there, faith began to heal again.

Act V: The Exile Who Spoke Truth – When One Voice Became a Storm

Back in Kampala, Annet Nakimuli , journalist and truth-seeker, received a tip.

A former church member had smuggled out video footage from inside the Deliverance Ministry.

It showed a boy being beaten while dozens prayed over him.

Crying.

Begging.

Calling for help.

Annet published the footage.

Headlines screamed:

“Faith or Torture? Ugandan Church Accused of ‘Exorcising’ Homosexuality.”

International outrage erupted.

Calls for sanctions grew louder.

But within Uganda, Pastor Kato responded with fury.

“These journalists are agents of Satan,” he declared. “They want to destroy our families, our values, our very souls.”

Yet something shifted.

People began asking questions.

“Why does God need to be feared so much?” “What kind of love demands hate?”

Even some members of Kato’s own church began to whisper:

“Maybe God doesn’t hate them.”

And whispers, as Annet knew, could become storms.

Act VI: The Fire That Could Not Be Contained – When the Flame Turned Back

One day, Joseph — the boy who had once held his lover’s hand in church — returned.

No longer silent.

No longer afraid.

He stood outside the New Light Revival Centre with a megaphone and a camera rolling.

He spoke into the wind:

“I was your brother. Your son. Your student. And you tried to erase me.”

The crowd gathered slowly.

Some jeered.

Others listened.

He continued:

“I am not a demon. I am not a disease. I am not a crime. I am a child of God.”

A woman in the crowd burst into tears.

A man stepped forward and hugged him.

And somewhere in the distance, Father Dominic watched and whispered:

“Maybe God has never left them.”

Act VII: The Fall of the Firebrand – When Zealotry Met Its End

The backlash was swift.

Donors withdrew support.

Foreign embassies issued statements.

Within weeks, leaks revealed the full extent of Kato’s ties to foreign evangelicals.

Emails surfaced showing how American lobbyists had coached him on messaging.

How they had paid for his rallies.

How they had shaped his sermons.

How they had turned faith into a business.

The world watched.

And Uganda began to turn.

Supporters abandoned him.

His followers questioned him.

His church shrank.

And one morning, Ezekiel Kato vanished.

Some say he fled to Rwanda.

Others claim he died in exile.

But his legacy remained — etched in fear, carved into laws, buried in graves.

Act VIII: The Chapel Without Walls – When Love Returned to Faith

Years later, in a quiet alley behind a tailor’s shop in Nakaseke, a new church rose.

Not in steeples or stained glass.

But in stories.

In songs.

In silence broken by truth.

They called themselves:

“The Chapel Without Walls.”

There, Joseph led discussions on faith and identity.

Tina Namutebi read poetry between prayers.

Annet shared her memoirs like scripture.

And Father Dominic, now older, still gentle, still brave, still believing, returned to preach one final sermon:

“Faith should unite, not divide. It should heal, not harm. And if God truly loved only the perfect, none of us would be saved.”

The crowd clapped.

Not loudly.

But lovingly.

And in that moment, Uganda remembered something it had nearly lost.

That faith was never meant to burn .

Only to light the way .

Epilogue: The Heart Cannot Hold Both Water and Fire – But It Can Choose Which It Lets Flow

Years passed.

The law remained — but its grip weakened.

Courts began hearing challenges.

Students debated whether homosexuality was truly un-African.

And in hidden corners of Uganda, churches quietly welcomed queer worshippers without judgment.

As the Swahili saying warns:

“Moyo mmoja hauwezi kushika maji na moto pamoja.”

“One heart cannot hold both water and fire.”

And yet, hearts change.

Beliefs evolve.

And sometimes, even the fiercest flames die down — leaving only warmth behind.

6. The Bench That Trembled: A Tale of Justice, Jails, and Jubilation

“Ɛneɛma nni haw nwɔfo.”

“No matter how long the night, dawn will come.”

In the heart of Kampala, beneath the jacaranda tree where truth often whispered louder than lies, sat Beatrice Were , a woman whose eyes had seen too much — arrests, betrayals, funerals held without names.

She was no stranger to pain.

Her brother had died in prison under the AHA.

Her best friend had been disowned by her family.

And she herself had once been beaten during a raid at a community meeting.

But today, she wore a suit.

Not for protection.

For war.

Today, Beatrice stood before the Constitutional Court of Uganda, not as a grieving sister or a frightened citizen — but as a lawyer.

And the law?

It trembled.

Act I: The Law That Wears a Mask – When Justice Played Hide-and-Seek

The Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) had arrived like thunder in a dry sky — loud, sudden, and merciless.

Passed in haste, signed with pride, enforced with cruelty.

It carried sentences heavier than stones.

Life imprisonment for “aggravated homosexuality.”

Twenty years for “promotion.”

Ten years for silence.

But hidden within its brutal clauses were something unexpected:

Loopholes.

Vague language. Missing procedures. Violations of constitutional rights.

Beatrice saw them.

So did Tina Namutebi , a young lawyer who had once been hunted for writing essays about queer life.

Together, they filed a petition that shook the nation.

“We challenge the AHA.”

Some called it madness.

Others called it treason.

But to those living in fear, it was hope.

Act II: The Goat Tethered by Another – When Laws Bound Without Understanding

The hearings began in a courtroom that smelled of old wood and older secrets.

Presided over by Justice Nantume — a stern woman with a reputation for fairness — the case unfolded like a slow-burning fire.

Beatrice spoke first.

“Article 8(1) says laws must be debated openly. This one was rushed through Parliament like a thief in the night.”

She continued:

“Article 27 protects privacy. Article 29, freedom of speech. Article 21, equality. Yet this law violates all three.”

Behind her, the crowd murmured.

Opposing counsel, a slick government lawyer named Mr. Tibamanya , leaned forward.

“These are foreign values masquerading as rights. We have our own ways.”

Tina shot back:

“Our Constitution is Ugandan. And it says we are all equal.”

Silence fell.

Then came the most daring line of all:

“If a goat is tethered by someone else, it doesn’t know how deep the river is. But we do. And we say this law drowns us.”

The judge scribbled notes.

The room buzzed.

And outside, the people watched.

Waiting.

Hoping.

Praying.

Act III: The Witnesses Who Spoke Truth – When Victims Became Voices

Day after day, the courtroom filled with testimonies.

One witness, a teacher named Joy Nakaseke , described how she was fired from her job after students overheard her telling a story about two men who loved each other.

“I didn’t promote anything,” she said. “I just told the truth.”

Another, a mother named Nakato , read aloud a letter from her son, still in prison:

“They call me names. They beat me. But I am not a criminal. I am a man who loves another man.”

There was also Joseph , the boy who had once held his boyfriend’s hand beneath Pastor Kato’s pulpit.

He testified:

“I was arrested for holding hands. My crime? Existing.”

His voice cracked.

So did hearts.

Even Mr. Tibamanya looked away.

Because some truths cannot be argued.

Only felt.

Act IV: The Bench That Held Firm – When Courage Met Corruption

Pressure mounted.

President Museveni issued warnings:

“Let the court remember who feeds them.”

Judges received anonymous threats.

Beatrice’s home was vandalised.

Tina’s phone was tapped.

Yet the trial continued.

Inside the courtroom, Beatrice showed video footage of parliamentary proceedings — showing MPs voting on the AHA without having read the full bill.

“How can you govern a country if you don’t even follow your own rules?” she asked.

Justice Nantume listened.

She didn’t speak much.

But when she did, the room fell silent.

“Laws must protect, not punish. Let us see whether this one does either.”

That single sentence sent ripples across the country.

State TV cut away mid-hearing.

Pastors ranted online.

But ordinary Ugandans?

They began asking questions.

“Did they even debate this law?”

“Is this really justice?”

“Or just politics dressed up as morality?”

Act V: The River That Ran Uphill – When International Law Entered Local Courts

To strengthen their case, Beatrice and Tina brought in international precedents.

They cited South Africa’s Constitution, which explicitly protected LGBTQ+ rights.

They referenced Kenya’s recent rulings allowing queer groups to register legally.

They quoted UN treaties Uganda had signed decades ago — promises now forgotten.

And then came the moment that stunned everyone.

A former diplomat — now retired — took the stand.

“Uganda pledged to uphold human dignity,” he said. “Not only abroad, but at home.”

He paused.

“And yet, we criminalise love.”

Gasps.

Clutching of rosaries.

Whispers of doubt.

Even Mr. Tibamanya hesitated before cross-examining him.

Because sometimes, the truth wears a tie and speaks softly.

And still changes everything.

Act VI: The Church That Whispered – When Faith Questioned Fear

Outside the courtroom, a quiet revolution stirred.

Father Dominic, once silenced for speaking compassion from the pulpit, released a pastoral letter titled:

“God Did Not Create Hate”

He wrote:

“Jesus touched lepers. He forgave prostitutes. If He walked among us now, would He cast stones — or offer shelter?”

The letter spread like wildfire.

Churches in Mbale quietly stopped preaching anti-LGBTQ+ sermons.

A bishop in Gulu invited queer youth to share their stories during Sunday service.

And in Jinja, a group of students staged a play titled:

“The Prodigal Son Returns”

It ended with a question:

“What if the lost son never left — he was simply made to feel unwelcome?”

The audience clapped.

Not loudly.

But lovingly.

Act VII: The Verdict That Wasn’t There – When Hope Waited

Weeks passed.

Then months.

Still, the judgment remained pending.

Activists grew restless.

Lawyers anxious.

The world impatient.

But Beatrice knew better.

“Justice may be slow,” she told Tina. “But it moves like water. It always finds its way.”

Tina smiled.

“Even through cracks in concrete?”

Beatrice nodded.

“Especially then.”

And so they waited.

With candles lit.

With voices stilled.

With faith unbroken.

Because in Uganda, the law had often been a weapon.

Now, it was becoming a shield.

Act VIII: The Dawn That Came – When the Bench Spoke

Finally, the day arrived.

Hundreds gathered outside the High Court.

Reporters jostled for position.

Twitter lit up with hashtags:

- #JusticeInKampala

- #QueerAndProudUG

- #TheBenchWillDecide

Inside, Justice Nantume rose.

She adjusted her glasses.

She cleared her throat.

And she spoke:

“This law, passed without proper consultation, with vague and cruel penalties, violates the spirit and letter of our Constitution. It discriminates. It punishes without reason. And it silences without cause.”

She paused.

“Therefore, I find sections of the Anti-Homosexuality Act unconstitutional and order that they be suspended pending further review.”

The courtroom erupted.

Some cheered.

Others gasped.

Beatrice closed her eyes.

Tina cried.

And somewhere in Luzira Prison, a man named Joseph heard the news through a smuggled radio.

He whispered:

“Maybe tomorrow, I walk free.”

Epilogue: The Night That Ends – When Dawn Is Real

Years later, the AHA was partially repealed.

Promotion laws remained — but enforcement weakened.

Courts ruled in favour of privacy.

Universities hosted debates on pre-colonial gender identities.

And in hidden corners of Uganda, queer youth found safe spaces — built not by politicians, but by people who believed in justice more than fear.

Beatrice became a national symbol of resistance and reform.

Tina opened a legal aid clinic for queer Ugandans.

Father Dominic founded a sanctuary known as:

“The Chapel Without Walls”

And under the jacaranda tree where it all began, children played.

Unafraid.

Unashamed.

Unpunished.

As the Ghanaian proverb reminds us:

“Ɛneɛma nni haw nwɔfo.”

“No matter how long the night, dawn will come.”

And in Uganda?

Dawn had finally risen.

7. The Trial of Annet: A Roar in Silence

“A roaring lion kills no one; it is the silent jungle that hides danger.”

In the city of Kampala, where the jacaranda trees bloom purple and the air smells like grilled meat and diesel fumes, Annet Kansiime sat in a cold, concrete cell beneath the High Court building. She had once been a university lecturer—beloved by students for her wit and feared by authorities for her words. Now, she was accused of “promoting homosexuality,” a crime punishable by twenty years in prison under Uganda’s notorious Anti-Homosexuality Act.

It was not a trial. It was a spectacle.

Reporters from Berlin to Bangkok watched as the Ugandan state dragged Annet into court like a trophy caught in a hunt not meant for sport, but for silence.

Her crime? Writing a series of essays titled “Love Without Labels” , published online and shared widely across East Africa. The pieces were poetic, unapologetic, and filled with stories of queer people living in the shadows—lovers hiding behind locked doors, families torn apart by shame, and hearts that beat proudly despite the threat of violence.

To the government, she was a traitor. To the world, she was a martyr in waiting.

Act I: The Accusation – A Circus of Morality

The courtroom was packed. Journalists jostled for space beside curious onlookers, foreign diplomats, and local pastors draped in robes stitched with scripture. The judge, a stern woman with eyes like polished stone, tried to maintain order while the prosecutor—a man named Mr. Tibamanya with a voice like a rusty gate—lectured the court on how Annet’s writings were “a homosexual virus infecting our moral bloodstream.”

Annet stood quietly, dressed in a simple blue dress, her hair tied back in a white headscarf. She looked more like someone attending church than standing trial for her life.

But when she spoke, the room fell silent.

“I did not write to promote or convert,” she said. “I wrote to reveal. To remind us that we are all made of love, fear, joy, and pain. That some among us live in cages built by others, and that the key lies in understanding—not punishment.”

Mr. Tibamanya sneered. “That sounds dangerously close to sedition.”

Laughter rippled through the crowd. Not out of amusement—but disbelief.

Act II: The Jungle Stirs – Whispers in the Shadows

Outside the courtroom, the streets told another story.

In the markets of Nakaseke, vendors whispered about Annet over baskets of matoke. In bars in Ntinda, young men debated her fate over Tusker beer. At Makerere University, students staged secret readings of her essays under the cover of night. And in hidden corners of the internet, queer youth found solace in her words, sharing them like sacred texts passed hand to hand.

Even within the legal system, cracks began to show. One of the junior prosecutors—a nervous young man named Ssebunya—was seen slipping notes to Annet’s lawyer, a fierce human rights advocate named Doreen Apio. Rumours spread that he had a cousin who was gay and had fled to Kenya after being disowned.

Meanwhile, Annet’s daughter, eight-year-old Lila, visited her mother every Sunday. They played games with stones and drew pictures of lions and stars. Lila didn’t understand what her mother had done wrong, only that she had made people angry by telling the truth.

One day, she asked, “Mummy, will you come home soon?”

Annet smiled. “Soon, little star. Soon.”

But she knew the truth: this wasn’t about justice. It was about control.

Act III: The Sentence – Fire and Ashes

When the verdict came, the world held its breath.

Guilty.

Twenty years.

The courtroom erupted. Some cheered. Others wept. Annet remained still. Only her eyes betrayed her—wide, not with fear, but fury.

As she was led away, she turned to the gallery and said, “If my silence would save me, I would have spoken nothing. But if my voice can free even one soul, then let my sentence be my song.”

She vanished into the darkness of Luzira Maximum Security Prison, where rats outnumbered books and hope was smuggled in through letters folded into bread rolls.

But outside, something unexpected happened.

People began to write.

Students, taxi drivers, farmers, teachers—all started publishing their own stories—on WhatsApp groups, Facebook walls, and anonymous blogs. They wrote about love, about fear, about being different in a world that demands sameness.

And slowly, steadily, the jungle roared.

Epilogue: The Lioness Returns

Two years later, international pressure mounted. Aid was withheld. Sanctions loomed. A new president took office, promising reform. Annet was released—thin, scarred, but unbowed.

She returned to a country both changed and unchanged. There were still laws that hated. Still voices that lied. But now there were also pens that fought, cameras that exposed, and hearts that dared.

At a small gathering in her honour, someone asked her:

“Was it worth it?”

She sipped tea, looked at Lila playing in the garden, and said:

“No one should have to pay such a price. But sometimes, you must burn down the barn to find the fire inside yourself.”

Then she added with a grin:

“And besides… lions don’t live forever. But legends do.”

8. Diplomatic Fallout and Economic Repercussions

The Great Banana Split: A Tale of Pride, Poverty, and Power

“If you do not know where you are going, any road will take you there.”

In the dusty town of Mbarara, under a sky so hot it seemed to sweat, an old man named Kintu Okot sat beneath a jacaranda tree, peeling matooke with a knife that had once been used to cut open goats—and possibly secrets.

He was retired now, once a respected civil servant, but like many things in Uganda, his pension had vanished into the void created by the Anti-Homosexuality Act and the international tantrum that followed.

“I used to get two sacks of posho every month,” he grumbled to no one in particular. “Now I get two bananas and a lecture about sovereignty.”

It all started when President Musoke—known affectionately as Big Mosi —signed the revised Anti-Homosexuality Act into law during a televised ceremony at State House. The event featured fireworks, gospel music, and a performance by the national choir dressed as angels. It ended with Big Mosi declaring:

“Let the West send their money elsewhere. We do not need dollars that smell of sin.”

And just like that, the world blinked.

Act I: The Storm Begins – When Donors Became Ghosts

Within weeks, the consequences came crashing down like a banana truck on a rainy hillside.

Foreign embassies issued visa bans on Ugandan officials suspected of human rights abuses. Development aid—once the lifeblood of hospitals, schools, and orphanages—was suspended. Trade restrictions were hinted at like a threat whispered behind a smile.

The World Bank paused a $200 million education grant. The United States froze HIV/AIDS funding. The European Union threatened sanctions over what they called “state-sponsored bigotry.”

But in Kampala, the mood was triumphant.

State TV ran headlines like:

“NO FOREIGN MASTER! UGANDA STANDS TALL!”

And the president’s press secretary, a man known only as Mr. Wacha (because nobody knew his real name), held daily briefings comparing Western outrage to “a jealous lover who can’t stand seeing Africa happy without them.”

People clapped. Some even danced.

But outside the capital, the truth began to rot.

Act II: The Rot Sets In – When Pride Could Not Pay the Bills

In a primary school in Jinja, Teacher Nambooze stood before her class of 76 children—all crammed into a room built for thirty.

She had no chalk. No books. No desks. Just a voice hoarse from repeating lessons she had memorised years ago.

One boy raised his hand.

“Ma’am, why don’t we have textbooks?”

She sighed.

“Because the government decided to protect our morals instead of our minds.”

Across town, in Mulago Hospital, a nurse named Sarah Mugisha watched a child die from malaria because the IV drip had run dry. The medicine was still listed in the system. But in reality, it was gone—cut off when foreign donors pulled out.

“Just another victim of politics,” she muttered, wiping tears with a blood-stained glove.

Meanwhile, in the lush suburbs of Kololo, Minister Kalyesubula hosted a dinner party. Lobster imported from Zanzibar. Wine from France. Cigars from Cuba.

His guests laughed, toasted, and quoted proverbs:

“The chicken that struts too proudly may forget how to fly.”

But none of them noticed the cracks forming in the foundation of their golden table.

Act III: The People Speak – A Symphony of Suffering and Satire

As the months passed, the disconnect between state rhetoric and street reality grew wider than Lake Victoria.

On social media, memes flooded timelines:

- A cartoon showed Big Mosi trying to arrest poverty with handcuffs shaped like crosses.

- Another depicted Mr. Wacha arguing with a goat over who was more full of hot air.

- A viral video showed a street comedian named Kasuku the Truthbird performing a skit titled:

“How to Build a School Without Money: A Step-by-Step Guide”

He ended with:

“Step One: Pray. Step Two: Wait. Step Three: Accept your children will grow up knowing more about homosexuality than mathematics.”

He was arrested the next day.

But his words lived on.

Underground radio stations began broadcasting satirical news shows. University students staged plays mocking the hypocrisy of leaders who preached morality while driving luxury cars paid for by taxpayers.

Even the churches were divided. One pastor left a fiery sermon:

“God does not bless a nation that starves its poor while feeding its pride!”

His congregation cheered. His church was closed within the week.

Act IV: The Breaking Point – When Sovereignty Met Starvation

Then came the rains.

And with them, floods.

Roads collapsed. Bridges washed away. Villages disappeared beneath rising waters.

But no foreign aid arrived.

No helicopters. No food drops. No tents.

Only silence.

In the village of Kabale, a mother named Nakaseke carried her sick child ten miles through mud and rain to find help. She collapsed at the door of a health centre that had no drugs, no electricity, and no doctor.

Her son died in her arms.

That night, she lit a candle and said to the wind:

“We fought colonialism to be free. But freedom means nothing if it cannot feed my child.”

Epilogue: The Mirror Cracks – But Still Reflects

Two years later, the economy limped along like a three-legged goat. Inflation soared. Unemployment worsened. Tourism dwindled. Investors fled.

President Musoke gave another speech.

“We remain steadfast,” he declared.

But behind him, the crowd was smaller. And quieter.

Some people still believed in his vision. Others simply feared speaking out.

Yet in the shadows, something stirred.

Students formed secret study groups. Farmers bartered goods across borders. Artists painted murals of lost children and broken promises.

And somewhere, deep in the forests near Katakwi, a group of elders gathered around a fire and told stories.

One elder spoke:

“Long ago, a man went into the forest to prove he could live alone. He chopped trees, built a house, and sang songs of independence. But soon, the rains came. And he found himself alone, cold, and hungry. Only then did he remember the proverb:

‘If you do not know where you are going, any road will take you there.’

So, brothers and sisters, let us ask: where are we going? And who among us has forgotten the way?”

9. The Whisperers: How Silence Began to Crack

“Ekyama ekikulu kiri mu nsi, kigenda obutereka.”

“Even the heaviest stone can be moved, one push at a time.”

In the narrow alleyways of Kisenyi, where the air smells of charcoal smoke and secrets, a small group of young people gathered every Thursday night. They called themselves The Whisperers —not because they were shy, but because they had no choice.

Their meetings took place in the back room of a tailor’s shop that doubled as a makeshift library. The walls were lined with second-hand books, many donated by foreign NGOs before the aid freeze. There was no electricity, so they read by candlelight or mobile phone torches. And always, someone stood watch at the door.

One of them was Tina Namutebi , a twenty-year-old student at Makerere University who wore her hair in tight braids and spoke like a storm trapped in a jar.

“I used to believe everything my pastor said,” she told the others during one meeting. “That being queer was a curse. That it was Western. That if you even thought about it, you’d burn in hell.”

She paused, then added, “But I met someone.”

There was a silence, thick with tension.

“She was beautiful,” Tina continued. “And kind. And Ugandan. And she loved me more than some people love their own children.”

No one clapped. No one gasped. But something shifted in the room. Like a stone being nudged ever so slightly.

Act I: The Voiceless Rise – A Rebellion in Silence

Across Kampala, whispers were becoming murmurs.

At the Uganda Martyrs Secondary School in Lubaga, a teacher named Mr. Ssenyonjo started sneaking excerpts from Annet Kansiime’s banned essays into his literature classes.

He called them “moral exercises.” His students called them “truth bombs.”

One day, he assigned an essay titled:

“If Love Is a Sin, Then Let Me Preach.”

A boy named Joseph wrote:

“My uncle has two wives and beats both. My cousin is gay and hides it for fear of shame. Which of them is truly immoral?”

Mr. Ssenyonjo gave him an A+.

Word spread.

Soon, students began writing their own stories—hidden inside poetry assignments, tucked into science notebooks, scribbled onto bathroom walls.

They weren’t loud. They weren’t violent.

But they were dangerous .

Because they made people think.

Act II: The Devil’s Playground – When Truth Becomes Crime

Meanwhile, in Ntinda, a nightclub known as The Velvet Vibe hosted secret drag shows every Friday night. The entrance was disguised as a car wash, and passwords changed weekly.

It was there that Kato , a soft-spoken fashion designer by day and a fierce performer by night, first stepped onto a stage wearing a dress stitched together from old kanga cloth and dreams.

He called himself Queen Nyota —meaning “star” in Swahili—and sang songs in Luganda, English, and pidgin, each one a cry for freedom wrapped in glitter and tears.

Between sets, he would speak.

“They say we are not African. That our love is borrowed. But tell me—when did joy become foreign? When did kindness become colonial?”

His voice echoed through the underground club scene. From there, it spilled into social media, hidden forums, encrypted chats.

And then came the raid.

Plainclothes police stormed The Velvet Vibe one rainy evening, beating patrons, seizing phones, dragging Kato away.

He vanished for weeks.

When he reappeared, he had lost three teeth and gained a thousand followers.

His video confession—released anonymously—went viral:

“I am still here. Bruised, yes. Broken, maybe. But not silenced.”

Act III: The Stone Begins to Move – One Push at a Time

Back in Kisenyi, the Whisperers grew bolder.

They started posting anonymous testimonials online under the hashtag #RealUganda .

One post read:

“I’m a soldier. I fight for my country. I also love men. Does that make me less loyal?”

Another:

“I am a mother. I pray every day. I also have a daughter who loves women. She is not cursed. She is brave.”

Some posts were shared thousands of times. Others were deleted within minutes. But they left fingerprints.

On Twitter, a journalist named Lena Akandu began publishing investigative pieces under the title:

“Who Decides What Is African?”

Her work exposed how conservative politicians and religious leaders profited from hate—selling fear like it was medicine.

She was threatened. Her office was vandalised. But she kept writing.

And readers kept reading.

Act IV: The Storm Breaks – When the Murmurs Become Thunder

Then came the tipping point.

A popular gospel preacher, Pastor Elijah Mwesigye , appeared on national television declaring:

“Homosexuality will destroy Uganda. We must cleanse this land.”

The next day, a video response surfaced. It was a montage of Ugandans—from taxi drivers to doctors, teachers to street vendors—saying:

“We know people like us exist. We see them. We love them. We protect them.”

It ended with a simple message:

“You cannot preach hate without showing your face.”

The video was viewed over ten million times.

Within days, Pastor Mwesigye resigned.

Not out of remorse—but out of fear.

Because suddenly, hate was no longer profitable.

Epilogue: The Heaviest Stone – Still Moving

Years later, the laws remained cruel. The prisons still held people for who they loved. But the tide had turned.

In classrooms, in bars, in WhatsApp groups and university halls, the whisperers had become speakers. The fearful had become fighters.

Tina Namutebi became a lawyer for LGBTQ+ rights.

Kato opened a safe house for queer youth, funded by pan-African solidarity networks.

And in the hills of Luweero, where war once raged and silence reigned, a new generation planted trees—each one carved with names of those who had dared to dream differently.

Underneath them, they etched a single saying:

“Ekyama ekikulu kiri mu nsi, kigenda obutereka.”

Even the heaviest stone can be moved.

One push at a time.

10. The Camera That Whispered: A Story of Kato and the Pictures That Would Not Be Silenced

“One bird cannot peck the sky clean, but many can.”

In the dim glow of a candlelit room behind a tailor’s shop in Nakulabye, Kato adjusted his camera lens like a surgeon preparing for surgery. His hands trembled—not from fear, but from purpose.

He was not just a photographer. He was a witness .

His latest subject was Joy , a nineteen-year-old lesbian who had fled her village after being accused of witchcraft when she refused to marry the chief’s son. She wore nothing but a borrowed dress and defiance.

Kato clicked the shutter.

The flash lit up the cracks in the walls, the dust in the air, and the fire in Joy’s eyes.

“Why are you doing this?” she asked.

“Because if we don’t tell our stories,” he said softly, “others will write them for us. And they won’t be kind.”

Act I: The Artist’s Curse – Painting Truth in a World Built on Lies

Kato had once been a celebrated fashion designer in Kampala. His work was worn by politicians’ wives, beauty queens, and gospel singers. But then came the night he kissed another man at a party in Kololo—and someone took a photo.

Within days, his contracts vanished. His studio was vandalised. His name became a whisper wrapped in shame.

But Kato did not vanish.

Instead, he picked up his camera and began telling stories that no one else dared to.

He started with portraits.

Queer Ugandans—each one framed not as victims, but as survivors , lovers , dreamers , warriors .

He gave them names like:

- “The Widow Who Loved Women”

- “The Priest Who Prayed in Secret”

- “The Soldier Who Sang in Silence”

Each photograph told a thousand words. Each face screamed louder than any protest.

And slowly, the world began to listen.

Act II: The Underground Gallery – Where Art Was a Weapon

Kato’s work could not be displayed openly. It would mean arrest—or worse.

So he created something new: The Invisible Museum .

A network of secret galleries hidden inside barbershops, basements, and abandoned churches. Entry required a password whispered only to those trusted.

At one such gallery beneath a mechanic’s garage in Ntinda, a young boy named Ssemakula stared at a portrait of a trans woman named Zawadi.

“She looks like my auntie,” he whispered.

“No,” said the curator, a former teacher named Doreen. “She is your auntie. Or she could be. We just never let her show it.”

Ssemakula returned every week. He started writing poetry. Then essays. Then songs.

His music spread like wildfire through schools and markets.

One line went viral:

“If love is a sin, then heaven must be full of saints.”

Act III: The Film That Shook the Nation – A Love Letter to the Unloved

Kato’s boldest project was a film called “Nyota ya Moyo” — Star of the Heart .