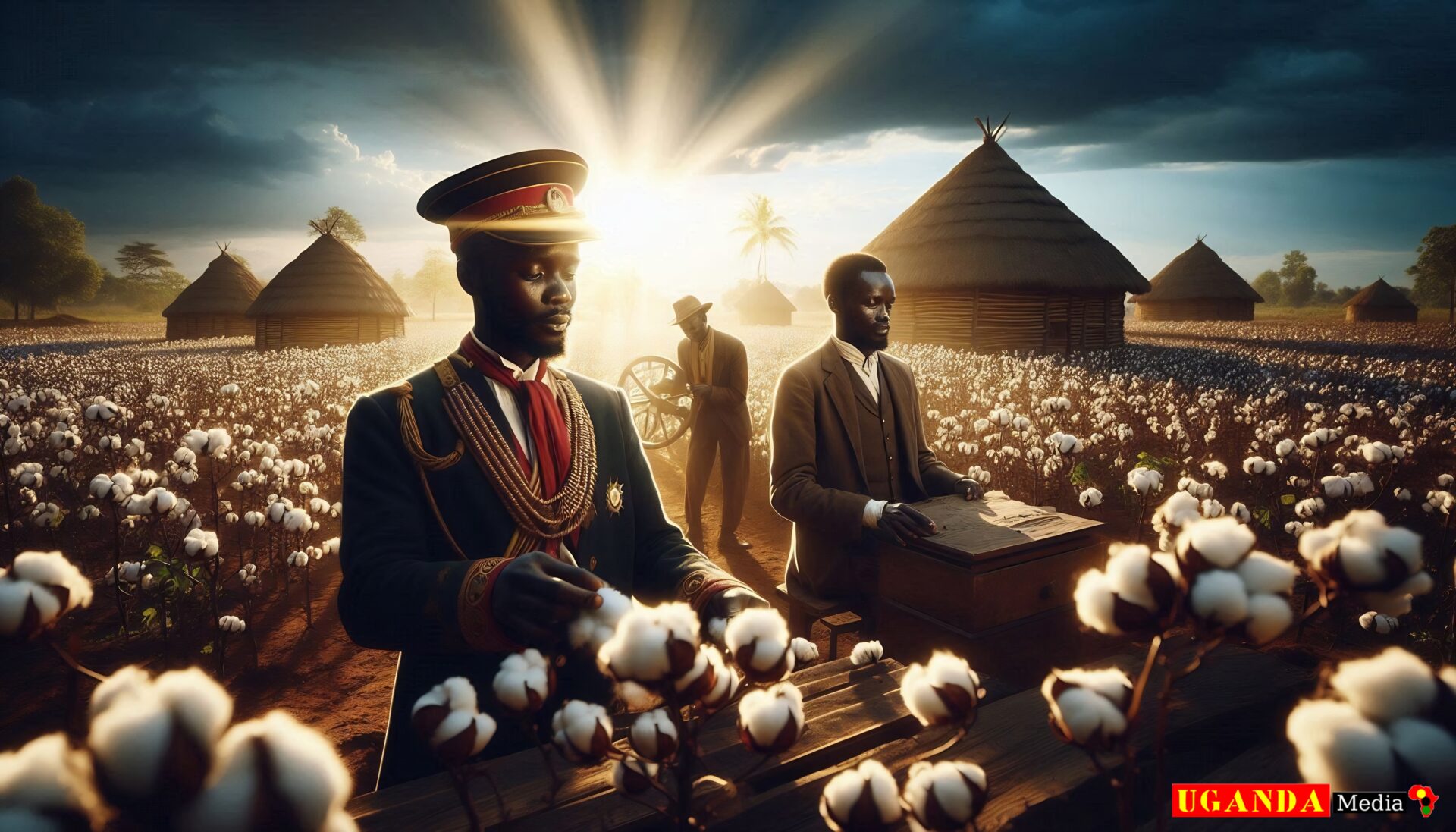

The History and Legacy of Commercial Cotton Growing in Busoga District, Uganda (1905–1923)

The story of commercial cotton growing in Busoga District, Uganda, between 1905 and 1923 is a fascinating tapestry of ambition, innovation, and resilience. This era marked the rise of an agricultural revolution driven by African growers, Indian traders, and colonial administrators, whose interactions shaped the economic and social fabric of the region. From the drumbeats echoing through Kamuli in 1911 to the bustling ginneries of Jinja, the period highlights both the triumphs and challenges of Uganda’s early cotton industry.

Key figures like Nanjibhai K. Mehta and Muljibhai P. Madvani , alongside educated chiefs such as Yosia Madiope and Ezekieri Wako , played pivotal roles in transforming Busoga into a hub of cotton production and industrial growth. However, this progress was not without contention. Discriminatory policies like the Five-Mile Radius Rule and the formation of European syndicates marginalised Indian entrepreneurs and African peasants, creating enduring legacies of inequality.

This article delves into the intricate dynamics of seed selection, soil preparation, pest management, and post-harvest practices that maximised cotton yields while addressing the socio-economic implications of monopolistic practices and restrictive legislation. By exploring these historical threads, we uncover valuable lessons on sustainable agriculture, equitable trade, and inclusive governance that remain relevant for contemporary debates around land use, labour rights, and fair trade in Uganda and beyond.

Introduction to Cotton Cultivation

The Fertile Soils and Favourable Climate of Busoga District

Nestled in eastern Uganda, Busoga District is a land of verdant beauty, blessed with fertile soils and a climate that seems almost tailor-made for agriculture. This region, crisscrossed by the mighty River Nile and dotted with lush marshlands, became the heartland of commercial cotton farming during the early 20th century. Its unique combination of natural resources made it an ideal location for cultivating this cash crop, which would eventually transform both the local economy and its social fabric.

Fertile Soils: A Farmer’s Dream

The soils of Busoga are predominantly black loams, renowned for their richness and ability to retain moisture—a characteristic particularly beneficial for crops like cotton. These deep, well-drained soils provided the perfect foundation for root development and sustained growth throughout the growing season. In addition to the black loams, other soil types across the district were equally capable of supporting robust cotton yields, provided they were properly managed through cultivation techniques such as ploughing and weeding.

For instance, areas near the riverbanks boasted alluvial deposits enriched by centuries of sedimentation, creating pockets of exceptionally productive farmland. Farmers working these lands often remarked on how effortlessly cotton plants thrived, producing bolls of remarkable size and quality. Such conditions gave rise to optimism among colonial administrators and local chiefs alike, who saw immense potential in harnessing Busoga’s agricultural promise.

A Favourable Climate: Sunshine and Rainfall in Harmony

In addition to its fertile soils, Busoga enjoys a tropical climate marked by distinct wet and dry seasons—an arrangement that proved highly conducive to cotton cultivation. The rainy season, typically spanning from March to May and again from September to November, ensured consistent moisture levels necessary for germination and early plant growth. Meanwhile, the dry spells between these periods allowed farmers to carry out essential tasks such as picking and drying the harvested cotton without fear of spoilage due to excessive rainfall.

Temperature variations within the district further enhanced its suitability for cotton farming. While some higher-altitude regions in Uganda struggled with cooler temperatures unsuitable for ripening cotton bolls, Busoga’s elevation remained low enough to maintain warmth throughout the year. This consistency in temperature promoted healthy plant development and extended the growing season, giving farmers ample time to nurture their crops.

Challenges Amidst Abundance

Despite these advantages, life as a cotton farmer in Busoga was not without its challenges. Pests and diseases posed significant threats, requiring vigilance and innovative solutions from growers. Moreover, the variability of rainfall patterns meant that timing sowing activities correctly was crucial; planting too early or too late could spell disaster for an entire harvest. To mitigate risks associated with unpredictable weather, agricultural officers introduced practices such as double sowings—a system where farmers planted two separate plots at different times, ensuring at least one would succeed regardless of seasonal fluctuations.

A Landscape Steeped in Tradition

Beyond its physical attributes, Busoga’s landscape carried cultural significance for its people. For generations, communities here had relied on subsistence farming, cultivating staples like matooke (bananas) alongside indigenous crops. Cotton represented a departure from tradition, introducing new rhythms and routines into daily life. Chiefs educated at prestigious institutions like Mengo High School and King’s College, Budo, played pivotal roles in bridging this transition, using their influence to encourage communal efforts and model best practices. Their leadership helped foster a sense of collective responsibility towards embracing cash crop agriculture while honouring age-old customs tied to the land.

Nature’s Bounty Meets Human Ingenuity

Busoga District’s fertile soils and favourable climate formed the bedrock upon which commercial cotton farming flourished during the early decades of the 20th century. Yet, what truly set this region apart was the synergy between nature’s bounty and human ingenuity. From the tireless labour of African cultivators to the entrepreneurial spirit of Indian traders and the strategic oversight of British colonial officials, each group contributed uniquely to shaping Busoga’s destiny. As fields of white cotton stretched across the horizon, they symbolised not just economic opportunity but also resilience, adaptability, and the enduring connection between humanity and the earth.

Colonial Influence: Encouraging Communal Cultivation Near Roadsides Under the Supervision of Educated Chiefs

In the early 20th century, colonial administrators in Uganda devised a strategy to promote commercial cotton cultivation that was both innovative and deeply rooted in their paternalistic approach to governance. This involved encouraging communal cultivation near roadsides, an initiative overseen by educated chiefs who served as intermediaries between the colonial government and local communities. The system was particularly prominent in districts like Busoga, where it became a hallmark of agricultural policy during the period from 1905 to 1923.

The Role of Educated Chiefs

At the heart of this initiative were the educated chiefs—individuals groomed in prestigious institutions such as Mengo High School and King’s College, Budo. These schools, located in Buganda, were designed to produce leaders loyal to colonial ideals while retaining influence within their own communities. For instance, figures like Yosia Madiope, Ezekieri Wako, and Zefania Nabikamba attended these institutions before returning to their districts to implement British policies.

These chiefs were not merely figureheads; they were expected to actively participate in promoting cash crop agriculture. Their education equipped them with administrative skills and an understanding of colonial expectations, making them ideal candidates for supervising communal farming efforts. By working alongside colonial officials, the chiefs helped bridge cultural divides and ensured compliance with directives aimed at transforming subsistence farmers into producers of exportable commodities.

Communal Cultivation Along Roadsides

One of the most striking features of the colonial approach was the emphasis on roadside cultivation. Colonial administrators recognized that poor communication networks posed significant challenges in reaching dispersed rural populations. To address this, they identified sites near major roads as central hubs for communal farming activities. These locations allowed easier access for monitoring progress, distributing instructions, and facilitating the transportation of harvested crops.

Every morning, the scene would unfold with remarkable consistency. Chiefs arrived at the designated roadside fields and announced their presence through traditional drumming, playing rhythms such as SsagaZa agalamidde (“morning sleepers wake up and work”). This ritual not only signalled the start of the day’s labour but also reinforced the authority of the chief over his community. Growers gathered under the watchful eyes of their leaders, receiving guidance on planting techniques, weeding schedules, and pest control measures.

To encourage regular attendance, chiefs often organised social incentives such as beer parties or communal meals. Such gatherings fostered camaraderie among participants and created a sense of collective responsibility towards the success of the project. While seemingly coercive, these practices reflected the broader colonial strategy of blending persuasion with subtle forms of coercion to achieve economic goals.

A Practical Solution Amidst Challenges

From a logistical standpoint, roadside cultivation addressed several practical concerns. First, it mitigated the difficulty of contacting farmers scattered across vast rural landscapes. By concentrating efforts along accessible routes, colonial officials could more easily oversee operations without needing extensive infrastructure. Second, it provided visibility—a visible demonstration of progress that could be showcased to visiting inspectors or higher authorities. Fields brimming with healthy cotton plants served as tangible evidence of successful intervention.

However, the system was not without its flaws. Critics argue that communal cultivation disrupted established patterns of land use and placed undue strain on growers, many of whom had limited experience with cash crops. Additionally, the focus on roadside plots sometimes neglected less accessible areas, leaving some farmers marginalized. Despite these shortcomings, the method proved effective enough to become a cornerstone of early colonial agricultural policy.

Symbolism of Chiefly Leadership

Beyond its practical applications, roadside cultivation carried symbolic weight. Chiefs were required to plant cotton near their residences, setting an example for their subjects. This practice operated on two levels: first, it demonstrated the feasibility—and profitability—of cash crop agriculture, inspiring ordinary “natives” to emulate their leaders. Second, it fostered competition among chiefs themselves, particularly in regions like Busoga, where many administrative roles were occupied by Baganda outsiders vying for favour with British officials.

For example, Kasibante, a regent for Yosia Nadiope of Bugabula, earned commendation from District Commissioner E.M. Isemonger for cultivating expansive fields of high-quality cotton near his headquarters. His meticulous organisation, including dividing fields into small rectangular patches managed by individual households, exemplified the kind of efficiency colonial administrators sought to replicate elsewhere. Such achievements underscored the dual role of chiefs as both enforcers of colonial policies and aspirational models for their communities.

Legacy of Colonial Influence

While the roadside cultivation model succeeded in establishing cotton as a viable cash crop in Busoga and beyond, it also laid bare the complexities of colonial rule. On one hand, it introduced new agricultural techniques and stimulated economic activity. On the other, it entrenched hierarchies and prioritised colonial interests over indigenous needs. The reliance on educated chiefs highlights the paradoxical nature of colonial administration: fostering leadership within African communities while simultaneously controlling and directing it to serve external agendas.

Ultimately, the encouragement of communal cultivation near roadsides under the supervision of educated chiefs represents a pivotal chapter in Uganda’s agricultural history. It reflects the intersection of tradition and modernity, coercion and cooperation, and local agency and imperial ambition—all set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing society striving to adapt to new realities.

The Role of Education: Highlighting the Significance of Institutions Like Mengo and Budo in Grooming Leaders Tasked with Promoting Cash Crops

In the early 20th century, as colonial administrators sought to transform Uganda’s agricultural landscape, they recognised the pivotal role education would play in shaping a new generation of African leaders. Institutions such as Mengo High School and King’s College, Budo—both located in Buganda—emerged as crucibles for grooming individuals who would serve as intermediaries between colonial authorities and local communities. These schools became instrumental in cultivating leaders tasked with promoting cash crops like cotton, particularly in regions like Busoga District where commercial agriculture was being actively encouraged.

Mengo and Budo: Pillars of Colonial-Era Education

Mengo High School, founded in 1906, and King’s College, Budo, established earlier in 1901, were among the premier educational institutions in colonial Uganda. Designed to provide Western-style education, these schools aimed to produce graduates fluent in English, familiar with British customs, and equipped with administrative skills. They were not merely centres of learning but also tools of colonial social engineering, intended to create a class of Africans loyal to British ideals while retaining influence within their own societies.

For example, prominent figures like Yosia Madiope, Ezekieri Wako, and Zefania Nabikamba attended these institutions before assuming leadership roles in Busoga. Their education included exposure to subjects such as history, geography, and rudimentary economics—fields that prepared them to understand and advocate for policies aligned with colonial economic objectives. By immersing students in an environment that emphasised discipline, punctuality, and adherence to authority, these schools instilled values deemed essential for implementing government directives at the grassroots level.

Producing Agents of Change

The primary objective of educating chiefs at Mengo and Budo was to equip them with the knowledge and skills necessary to promote cash crop cultivation effectively. Chiefs were expected to act as agents of change, bridging cultural divides and ensuring compliance with colonial agricultural policies. For instance, after completing his studies at Mengo (1900–1905) and later at Budo (1906–1908), Yosia Madiope returned to Busoga fully prepared to oversee communal cotton farming efforts. Similarly, Ezekieri Wako and Yekonia Lubogo, who studied at Budo during the 1910s, brought back insights into modern agricultural techniques and organisational strategies that proved invaluable in mobilising rural populations.

These educated leaders played a dual role. On one hand, they served as representatives of colonial authority, tasked with enforcing regulations related to land use, labour, and crop production. On the other, they acted as mediators, interpreting and sometimes tempering colonial demands to align with local realities. This unique position allowed them to wield considerable influence over how cash crop initiatives were implemented on the ground.

Promoting Cotton Cultivation Through Educated Leadership

One of the most visible ways in which educated chiefs contributed to promoting cotton cultivation was through their active involvement in roadside communal farming projects. As previously noted, colonial administrators insisted that cotton initially be grown communally near roadsides under the supervision of these leaders. Every morning, chiefs arrived at designated sites, announcing their presence through traditional drumming rhythms like SsagaZa agalamidde (“morning sleepers wake up and work”). This ritual signalled the start of daily labour and reinforced the authority of the chief over his community.

Educated chiefs excelled in organising and motivating growers. For instance, Kasibante—a regent for Yosia Nadiope of Bugabula—earned commendation from District Commissioner E.M. Isemonger for cultivating expansive fields of high-quality cotton near his headquarters. His meticulous organisation, including dividing fields into small rectangular patches managed by individual households, exemplified the kind of efficiency colonial administrators sought to replicate elsewhere. Such achievements underscored the importance of education in equipping leaders with the ability to implement complex agricultural systems successfully.

Moreover, residence-grown cotton served as a powerful tool for inspiring ordinary “natives” to adopt cash crop agriculture. Chiefs were required to plant cotton near their homes, setting an example for their subjects. This practice operated on two levels: first, it demonstrated the feasibility—and profitability—of cash crop agriculture, encouraging ordinary farmers to emulate their leaders; second, it fostered competition among the chiefs themselves, particularly in regions like Busoga, where many administrative roles were occupied by Baganda outsiders vying for favour with British officials.

Challenges and Criticisms

While the contributions of educated chiefs cannot be overstated, this system was not without its challenges. Critics argue that the emphasis on Western-style education created a disconnect between these leaders and their communities. Many ordinary Basoga viewed these educated elites as out of touch with traditional ways of life, leading to tensions and resistance against imposed agricultural practices. Additionally, the competitive nature of the system sometimes exacerbated rivalries among chiefs, diverting focus away from collective progress toward personal advancement.

Furthermore, the paternalistic approach inherent in colonial education meant that chiefs were often trained to prioritise British interests over indigenous needs. While they gained valuable skills and knowledge, they also became enforcers of policies that sometimes disadvantaged their own people. For instance, when open markets were introduced in 1913, ostensibly to protect African growers from unscrupulous Indian traders, the move inadvertently deprived many farmers of opportunities to participate in other aspects of the cotton industry. Educated chiefs found themselves caught between implementing such policies and addressing the grievances of their constituents.

Legacy of Educational Influence

Despite these challenges, the legacy of institutions like Mengo and Budo endures in Uganda’s agricultural history. By producing leaders capable of navigating both colonial and local contexts, these schools laid the foundation for a model of governance that blended tradition with modernity. The emphasis on education as a means of promoting economic development continues to resonate today, serving as a reminder of the enduring impact of human capital investment.

Ultimately, the significance of Mengo and Budo lies not just in the individuals they produced but in the broader societal shifts they facilitated. Through their graduates, these institutions helped usher in an era of transformation, where cash crops like cotton became central to Uganda’s economy and identity. Yet, they also highlight the complexities of colonial rule, revealing how education could simultaneously empower and constrain those it sought to uplift.

Chiefs as Role Models: How Residence-Grown Cotton Served as a Model for Ordinary “Natives” to Adopt Cash Crop Agriculture

In the early 20th century, one of the most effective strategies employed by colonial administrators in Uganda to promote cash crop agriculture—particularly cotton cultivation—was the requirement for chiefs to grow cotton near their residences. This initiative, implemented across regions like Busoga District, was designed not only to demonstrate the feasibility and profitability of cash crops but also to inspire ordinary “natives” to follow suit. By positioning chiefs as role models, colonial authorities sought to bridge cultural divides and encourage the widespread adoption of commercial farming practices. The success of this approach rested on the dual objectives of impressing local communities and fostering healthy competition among leaders.

A Visible Demonstration of Feasibility

Residence-grown cotton served as a tangible example of how cash crops could be successfully integrated into traditional agricultural systems. Chiefs, who were often educated at prestigious institutions such as Mengo High School or King’s College, Budo, were expected to lead by example. Their proximity to colonial ideals and modern agricultural techniques made them uniquely positioned to experiment with and showcase the benefits of cotton cultivation.

For instance, Kasibante—a regent for Yosia Nadiope of Bugabula—cultivated approximately 50 acres of high-quality cotton near his headquarters. His fields were meticulously organized into small rectangular patches assigned to individual households, each overseen by designated supervisors to ensure optimal maintenance. When District Commissioner E.M. Isemonger visited these fields, he praised them as “the best kept and healthiest field I have seen in the country,” predicting a bountiful harvest. Such visible successes demonstrated that cotton could thrive under proper management, providing a compelling argument for ordinary farmers to emulate their leaders.

The presence of thriving cotton plots near chief’s residences acted as a constant reminder of its potential. Every morning, as chiefs arrived at communal roadside sites to oversee collective efforts, they brought with them stories of progress from their own lands. These narratives reinforced the idea that adopting cash crop agriculture was not only possible but advantageous. For many Basoga farmers accustomed to subsistence farming, seeing their leaders achieve tangible results helped demystify the transition to commercial agriculture.

Fostering Competition Among Chiefs

Beyond inspiring ordinary growers, residence-grown cotton also encouraged rivalry among chiefs themselves. In Busoga, where administrative roles between 1900 and 1915 were largely occupied by Baganda outsiders competing for favour with British officials, cultivating impressive cotton fields became a means of asserting authority and securing promotions. Chiefs understood that their performance in promoting cash crops directly influenced their standing within the colonial hierarchy.

Kasibante’s commendation by District Commissioner Isemonger is a case in point. His dedication to producing fine cotton earned him recognition and likely bolstered his reputation among both colonial superiors and local constituents. Similarly, other prominent figures like Yosia Madiope, Ezekieri Wako, and Zefania Nabikamba leveraged their education and administrative skills to excel in cotton cultivation, further solidifying their positions as influential leaders.

This competitive dynamic had cascading effects on ordinary “natives.” As chiefs vied to outperform one another, they invested more resources and effort into demonstrating the viability of cash crops. Consequently, their subjects benefited from improved knowledge sharing, better access to quality seeds, and enhanced organizational structures—all of which facilitated smoother transitions to cash crop agriculture.

Inspiring Confidence Through Leadership

The principle of “follow my leader” underpinned much of the colonial strategy. Chiefs were not merely figureheads; they embodied the values and practices colonial administrators wished to instil in rural populations. By planting cotton near their homes, they provided a relatable model for ordinary Basoga farmers. Seeing respected community leaders engage in cash crop cultivation reassured growers that embracing new agricultural methods would not alienate them from their traditions, but rather enhance their livelihoods.

Moreover, residence-grown cotton allowed chiefs to address practical concerns firsthand. They could identify challenges related to soil preparation, pest control, or harvesting and devise solutions tailored to local conditions. This hands-on experience enabled them to offer informed guidance to their subjects, fostering trust and cooperation. Chiefs’ ability to balance innovation with tradition proved instrumental in overcoming resistance to change.

Challenges and Criticisms

While residence-grown cotton achieved significant successes, it was not without its drawbacks. Critics argue that the emphasis on chiefs as role models sometimes created unrealistic expectations. Many ordinary Basoga farmers lacked the resources, expertise, or support networks available to their leaders, making it difficult to replicate similar outcomes. Additionally, the competitive nature of the system occasionally exacerbated tensions among chiefs, diverting focus away from collective progress toward personal advancement.

Furthermore, some viewed the requirement for chiefs to cultivate cotton near their residences as coercive. While intended to inspire confidence, it could also be perceived as an imposition, undermining the very trust colonial authorities sought to build. Despite these challenges, however, the overall impact of residence-grown cotton cannot be overstated. It laid the groundwork for broader acceptance of cash crop agriculture and contributed significantly to the economic transformation of regions like Busoga.

Legacy of Chiefs as Agricultural Pioneers

The legacy of residence-grown cotton extends far beyond the early 20th century. By positioning chiefs as pioneers in cash crop agriculture, colonial administrators inadvertently empowered a generation of leaders capable of navigating both traditional and modern contexts. Their contributions helped establish cotton as a cornerstone of Uganda’s economy, shaping policies and practices that continue to influence agricultural development today.

Ultimately, residence-grown cotton exemplifies the intersection of leadership, innovation, and resilience. Through their fields, chiefs communicated a powerful message: that embracing cash crop agriculture offered opportunities for growth and prosperity. Whether through Kasibante’s meticulously managed plots or Yosia Madiope’s commitment to communal farming, these leaders left an indelible mark on Uganda’s agricultural history—a testament to the enduring power of role models in driving societal change.

Indian Traders and Their Impact

Pioneering Efforts: How Indian Merchants Ventured Deep into Rural Uganda Despite Risks from Disease, Lack of Infrastructure, and Cultural Barriers

The story of Indian merchants in Uganda during the early 20th century is one of remarkable resilience, entrepreneurial spirit, and unwavering determination. These pioneers ventured deep into rural areas—often far removed from established towns or colonial outposts—to establish trade networks that would transform the country’s economy. Their efforts were particularly evident in the cotton industry, where they played a pivotal role in stimulating production, connecting African growers to global markets, and laying the groundwork for industrial growth. Yet, their journey was fraught with significant challenges, including widespread disease, inadequate infrastructure, and profound cultural barriers.

Venturing Into the Unknown

Indian merchants, many of whom hailed from Gujarat in western India, arrived in Uganda as immigrants seeking economic opportunities. They were drawn by the promise of untapped potential in East Africa’s burgeoning agricultural sector. Cotton, which had been introduced as a cash crop in the early 1900s, became a focal point of their enterprise. However, reaching the source of this valuable commodity required venturing into some of the most remote and inhospitable regions of Uganda.

In districts like Busoga, Teso, and Lango, Indian traders travelled on foot, by bicycle, or occasionally by rudimentary carts to reach scattered homesteads where African farmers cultivated cotton. The terrain they traversed was often rugged and marshy, making travel arduous and time-consuming. For example, the dense forests and swamps surrounding Lake Kyoga posed formidable obstacles, while the savannas of eastern Uganda offered little shelter from harsh weather conditions. Despite these difficulties, Indian merchants persisted, driven by the prospect of securing raw materials at competitive prices.

Their willingness to go “deep into the countryside” set them apart from European traders, who largely confined themselves to urban centres or relied on intermediaries. This hands-on approach allowed Indians to build direct relationships with African growers, fostering trust and ensuring a steady supply of high-quality cotton. As noted in historical accounts, Indian merchants were described as “entrepreneurs beyond comparison,” whose ventures shortened distances growers had to walk to sell their produce and reduced exposure risks for harvested cotton.

Facing Health Risks

One of the gravest dangers faced by Indian merchants was the prevalence of tropical diseases such as malaria, sleeping sickness, and dysentery. Medical facilities in rural Uganda were virtually nonexistent during the early 20th century, leaving traders vulnerable to illness without recourse to proper treatment. Malaria, transmitted through mosquito bites, was especially rampant in low-lying areas near rivers and lakes, including parts of Busoga District. Many Indian merchants fell victim to these diseases, yet their determination remained unshaken.

For instance, Nanjibhai K. Mehta, who started as a simple shopkeeper in Kamuli, experimented with cotton cultivation in the backyards of his store before expanding into buying and ginning operations. His success came not only from business acumen but also from enduring the physical toll of working in challenging environments. Similarly, Muljibhai P. Madvani, another prominent figure in Uganda’s economic history, overcame health risks and logistical hurdles to establish himself as a leading entrepreneur in the cotton trade.

These individuals exemplified the courage and tenacity required to thrive in an environment where even basic necessities like clean water and sanitation were scarce. Their ability to adapt to local conditions and persevere despite health threats underscores their pioneering spirit.

Navigating Infrastructure Deficits

Beyond health risks, Indian merchants contended with severe deficiencies in infrastructure. Roads were either non-existent or poorly maintained, isolating rural communities from major trading hubs. Transportation of goods, whether it involved moving bales of cotton to ginneries or delivering supplies to farmers, was a labour-intensive process that tested the limits of human endurance.

To overcome these limitations, Indian traders innovated. They established ginneries closer to growing regions, thereby reducing the distance farmers needed to transport their harvests. Alidina Visram, for example, erected ginneries at Jinja in 1911/12, strategically positioning them to serve nearby districts. This initiative not only streamlined operations but also created employment opportunities for locals, further integrating Indian enterprises into the fabric of Ugandan society.

However, the lack of police protection added another layer of complexity. Merchants operating in remote areas frequently encountered banditry and theft, forcing them to rely on personal vigilance or informal agreements with local leaders for safety. In some cases, traders armed themselves or hired escorts to safeguard their journeys—a testament to the lengths they were willing to go to protect their investments.

Overcoming Cultural Barriers

Perhaps the most daunting challenge faced by Indian merchants was navigating cultural barriers. Upon arriving in Uganda, many found themselves in unfamiliar social landscapes characterized by diverse languages, customs, and traditions. Establishing rapport with African communities required patience, diplomacy, and a genuine understanding of local values.

Initially, interactions between Indian traders and African growers were marked by mutual curiosity and cautious cooperation. Over time, however, shared economic interests fostered stronger bonds. Indian merchants learned local dialects, participated in community gatherings, and adapted their business practices to align with indigenous norms. For example, offering small gifts or hosting meals became common strategies for building goodwill among farmers.

Despite these efforts, tensions occasionally arose due to misunderstandings or perceived exploitation. Critics accused some Indian traders of paying unfairly low prices for cotton or charging exorbitant fees for ginning services. While such allegations were not universal, they highlight the delicate balance Indian merchants had to strike between profitability and ethical conduct.

Legacy of Resilience

The pioneering efforts of Indian merchants left an indelible mark on Uganda’s economic landscape. By venturing into rural areas, they bridged gaps in the supply chain, stimulated cotton production, and contributed to the rise of industries such as sugar manufacturing. Figures like Nanjibhai Mehta and Muljibhai Madvani epitomized the transformative power of entrepreneurship, leveraging their experiences in the cotton trade to diversify into other sectors.

Moreover, their contributions extended beyond economics. Indian merchants helped introduce new technologies, fostered cross-cultural exchanges, and laid the foundation for future generations of entrepreneurs. Their legacy serves as a reminder of the extraordinary achievements possible when determination meets opportunity—even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

In conclusion, the story of Indian merchants in rural Uganda is one of grit, innovation, and perseverance. Their willingness to confront disease, navigate infrastructure deficits, and overcome cultural barriers underscores their pivotal role in shaping the nation’s agricultural and industrial development. Through their endeavours, they enriched themselves and contributed to the broader narrative of Uganda’s progress during a transformative era.

Economic Contributions: How Indians Stimulated Cotton Production Through Ginneries and Middleman Activities

The economic contributions of Indian merchants to the development of Uganda’s cotton industry during the early 20th century are both profound and multifaceted. Through their establishment of ginneries and their role as middlemen, Indians played a pivotal role in stimulating cotton production, connecting African growers to global markets, and laying the groundwork for industrial growth. Their efforts transformed the agricultural landscape and reshaped the socio-economic fabric of regions like Busoga District, where cotton became a cornerstone of local economies.

Establishing Ginneries: A Catalyst for Growth

One of the most significant ways in which Indian merchants stimulated cotton production was through the construction of ginneries—facilities designed to separate cotton fibres from seeds. Prior to the introduction of these facilities, African farmers faced immense challenges in processing their harvests. Cotton bolls, once picked, comprised roughly two-thirds seeds—an unmarketable waste product at the time. Without access to efficient ginning technology, farmers were forced to transport raw cotton over long distances to sell it, exposing their produce to damage and reducing its market value.

Indian entrepreneurs recognized this gap in the supply chain and moved swiftly to address it. For example, Alidina Visram, a prominent trader, established ginneries in Jinja as early as 1911–1912. These strategically located facilities shortened the distance growers had to travel to sell their cotton, thereby encouraging increased participation in the cash crop economy. Similarly, Nanjibhai K. Mehta, who began as a simple shopkeeper in Kamuli, expanded his operations to include ginneries in Kamuli and Busembatia after amassing substantial profits from cotton trading during World War I. His ventures facilitated cotton processing and provided employment opportunities for locals, further integrating Indian enterprises into Ugandan society.

By erecting ginneries closer to growing regions, Indian merchants effectively reduced logistical barriers for African farmers. This proximity allowed growers to reduce the time during which their cotton remained exposed to environmental risks such as rain or pests. Moreover, the presence of multiple ginneries fostered healthy competition among buyers, driving up prices even during periods when global demand fluctuated. As a result, Indian-owned ginneries became a familiar feature across Uganda, with nearly 90% of the country’s ginning capacity controlled by Indians by the mid-1920s.

Middleman Activities: Bridging Growers and Markets

In addition to operating ginneries, Indian merchants served as indispensable intermediaries between African growers and international markets. Known locally as “middlemen,” they bought raw cotton directly from farmers, often venturing deep into rural areas despite formidable risks such as disease, lack of police protection, and challenging terrain. Their willingness to penetrate remote regions ensured that no grower was left without access to a buyer, thereby bolstering overall production levels.

The role of middlemen extended beyond mere purchasing. They introduced innovative practices that streamlined the marketing process, making it easier for farmers to participate in the broader economy. For instance, the double sowing system adopted in Teso district—a method where each cultivator maintained two plots sown at different times—was likely influenced by interactions with Indian traders. By ensuring that at least one plot adapted to seasonal variability, this approach minimized the risk of total crop failure and maximised yields.

Furthermore, Indian middlemen helped popularise Ugandan cotton on the global stage. Beginning in 1914, they successfully introduced Uganda cotton to Indian mills, highlighting its suitability for spinning finer fibres. The subsequent rise in exports to Bombay created a virtuous cycle: increased demand from India incentivised higher production in Uganda, while improved transportation networks facilitated smoother trade flows. Japan, too, emerged as a ready buyer of surplus cotton from the Bombay market, underscoring the far-reaching impact of Indian entrepreneurial efforts.

Economic Prosperity and Social Transformation

The economic contributions of Indian merchants were not confined to infrastructure and trade alone; they also catalysed broader social transformations within Ugandan communities. As cotton cultivation gained traction, many African households experienced unprecedented prosperity. Evidence of this newfound wealth surfaced during the 1920s, with reports indicating that some growers could afford luxuries previously unimaginable. Chiefs’ salaries and pensions, for example, saw significant increases due to heightened productivity in their domains.

Indian merchants themselves reaped considerable rewards from their involvement in the cotton trade. Figures like Muljibhai P. Madvani leveraged their profits to diversify into other sectors, establishing sugar estates at Kakira during the 1920s. Likewise, Nanjibhai Mehta’s success in cotton enabled him to build the Lugazi sugar works in 1923, marking the beginning of Uganda’s modern agro-industrial sector. These achievements underscored the transformative power of entrepreneurship, demonstrating how individual initiative could drive collective progress.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite their undeniable contributions, Indian merchants faced criticism from various quarters. Some accused them of exploiting African growers by paying unfairly low prices for raw cotton and charging exorbitant fees for ginning services. While such allegations were not universal, they highlighted the delicate balance Indian traders had to strike between profitability and ethical conduct. Additionally, the British colonial government viewed Indian dominance in the cotton trade with suspicion, fearing that it undermined Lancashire’s interests by diverting high-quality fibres to Indian mills.

To counteract this perceived threat, the colonial administration implemented restrictive measures such as the Uganda Cotton Rules of 1918 and the Five-Mile Radius Policy of 1919. These regulations severely curtailed Indian activities, granting artificial protection to smaller European-owned ginneries in interior districts while cutting off supplies to larger Indian-owned facilities at ports like Jinja and Kampala. Despite these obstacles, however, Indian merchants continued to innovate and adapt, maintaining their influence over the industry well into the interwar period.

Legacy of Economic Contributions

The legacy of Indian merchants in Uganda’s cotton industry is one of resilience, ingenuity, and enduring impact. By establishing ginneries and serving as middlemen, they bridged critical gaps in the supply chain, stimulated production, and connected African growers to global markets. Their efforts laid the foundation for future generations of entrepreneurs and contributed significantly to Uganda’s economic development.

Ultimately, the story of Indian contributions to cotton production serves as a testament to the extraordinary achievements possible when determination meets opportunity—even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. Through their endeavours, Indian merchants not only enriched themselves but also enriched the nation, leaving an indelible mark on Uganda’s history.

Success Stories: Profiling Entrepreneurs Like Nanjibhai K. Mehta and Muljibhai P. Madvani, Whose Ventures Laid Foundations for Future Industries

The story of commercial cotton growing in Uganda during the early 20th century is incomplete without highlighting the remarkable achievements of pioneering entrepreneurs such as Nanjibhai K. Mehta and Muljibhai P. Madvani. These individuals not only rose to prominence through their involvement in the cotton trade but also leveraged their successes to establish industries that would shape Uganda’s economic landscape for decades to come. Their journeys exemplify resilience, vision, and an unwavering commitment to progress—qualities that continue to inspire generations.

Nanjibhai K. Mehta: From Humble Beginnings to Industrial Magnate

Nanjibhai K. Mehta’s journey began in Kamuli, a bustling town in Busoga District, where he initially operated a modest shop catering to local needs. However, his entrepreneurial spirit soon led him to experiment with cotton cultivation in the backyards of his shop. This venture proved so successful that it marked the beginning of a transformative odyssey into the heart of Uganda’s agricultural economy.

During World War I, Mehta capitalized on the global demand for cotton by purchasing raw cotton directly from African growers at competitive prices. His timing was impeccable; shipping disruptions severely impacted Britain’s ability to transport goods between its colonies, creating opportunities for Indian merchants with direct access to East Africa. By the war’s end, Mehta had amassed substantial wealth, enabling him to expand his operations significantly.

In 1918, he erected ginneries in Kamuli and Busembatia, strategically positioning them near key growing regions. These facilities streamlined the processing of cotton and provided employment opportunities for locals, further integrating his enterprises into Ugandan society. The profits generated from these ventures laid the groundwork for even more ambitious projects. In 1923, Mehta founded the Lugazi Sugar Works, marking the dawn of modern agro-industrial development in Uganda.

Mehta’s success was not merely a personal triumph; it represented a broader shift towards industrialization in the region. His ability to identify gaps in the supply chain—from cultivation to processing—and address them effectively demonstrated his acute business acumen. Moreover, his investments in infrastructure, such as roads and storage facilities, facilitated smoother trade flows, benefiting both growers and other stakeholders.

Reflecting on his life in Dream Half Expressed (1966), Mehta recounted how his early struggles shaped his approach to entrepreneurship. He emphasized the importance of perseverance, adaptability, and ethical conduct in building sustainable businesses. Through his efforts, he enriched himself and contributed to the economic empowerment of countless Ugandans.

Muljibhai P. Madvani: A Visionary Leader in Agribusiness

Another towering figure in Uganda’s economic history is Muljibhai P. Madvani, whose contributions to the cotton industry paved the way for the establishment of one of the country’s largest sugar estates. Like Mehta, Madvani hailed from Gujarat and arrived in Uganda seeking opportunities. Initially managing Vitaldas Haridas and Company at Iganga, he quickly distinguished himself as a shrewd trader with a keen eye for innovation.

Madvani’s breakthrough came during the First World War when he, too, capitalized on the surge in demand for Ugandan cotton. His meticulous approach to buying and marketing earned him a reputation for fairness and reliability among African growers. As his profits grew, so did his ambitions. During the 1920s, Madvani invested heavily in the construction of ginneries, ensuring that growers had convenient access to processing facilities. This move enhanced efficiency and strengthened his ties with local communities.

However, Madvani’s most enduring legacy lies in his decision to diversify into sugar production. Recognizing the potential of sugarcane cultivation in eastern Uganda, he established a sprawling estate at Kakira during the 1920s. This venture transformed Kakira into a hub of agricultural and industrial activity, generating thousands of jobs and stimulating ancillary industries such as transportation and manufacturing.

Madvani’s leadership style was characterized by pragmatism and foresight. He understood the importance of aligning his interests with those of the communities in which he operated. For instance, he introduced welfare programs for workers, including healthcare and education initiatives, fostering loyalty and goodwill. His emphasis on corporate social responsibility set a precedent for future entrepreneurs, demonstrating that profitability and social impact could coexist harmoniously.

Foundations for Future Industries

The contributions of Mehta and Madvani extended far beyond their immediate successes in the cotton trade. Both men played pivotal roles in laying the foundations for Uganda’s industrial sector, particularly in agriculture-based manufacturing. Their investments in ginneries, sugar estates, and related infrastructure created ecosystems that supported diverse economic activities.

For example, the Lugazi Sugar Works established by Mehta became a cornerstone of Uganda’s sugar industry, supplying both domestic and international markets. Similarly, Madvani’s Kakira estate emerged as a model of integrated agribusiness, combining cultivation, processing, and distribution under one umbrella. These ventures not only diversified Uganda’s export portfolio but also reduced dependency on imported goods, bolstering the nation’s self-sufficiency.

Moreover, the ripple effects of their achievements were felt across various sectors. The expansion of cotton ginneries and sugar estates spurred demand for skilled labor, encouraging migration from India and other parts of Uganda. Artisans, engineers, and administrative workers found ample opportunities to contribute their expertise, further enriching the socio-economic fabric of the region.

Challenges and Resilience

Despite their successes, Mehta and Madvani faced significant challenges along the way. Colonial policies, such as the Uganda Cotton Rules of 1918 and the Five-Mile Radius Policy of 1919, sought to curb Indian dominance in the cotton trade by favouring European-owned enterprises. These regulations severely restricted access to supplies and markets, threatening the viability of their operations.

In response, both entrepreneurs adapted strategically. They diversified their portfolios, ventured into new industries, and advocated for fairer treatment through organizations like the Free Traders’ Union of Uganda. Their resilience in the face of adversity serves as a testament to their determination to overcome obstacles and leave a lasting legacy.

Legacy and Inspiration

Today, the legacies of Nanjibhai K. Mehta and Muljibhai P. Madvani endure as symbols of what can be achieved through hard work, innovation, and collaboration. Their stories underscore the transformative power of entrepreneurship, illustrating how individual initiative can drive collective progress. Through their ventures, they built prosperous businesses and contributed to the broader narrative of Uganda’s development during a transformative era.

Ultimately, the success stories of Mehta and Madvani remind us that true leadership transcends profit margins. It involves creating value for society, empowering communities, and leaving behind institutions that stand the test of time. As Uganda continues to navigate its path toward economic growth, the lessons imparted by these pioneers remain as relevant today as they were a century ago.

Cultural Exchange: Analysing How Interactions Between Indians, Africans, and Europeans Created a Unique Socio-economic Dynamic

The interactions between Indians, Africans, and Europeans in colonial Uganda during the early 20th century were not merely transactions of trade or labour; they represented a profound cultural exchange that shaped the socio-economic fabric of the region. These interactions, particularly within the context of the cotton industry, created a unique dynamic marked by collaboration, tension, adaptation, and mutual influence. This dynamic was especially evident in districts like Busoga, where the convergence of these three groups played a pivotal role in transforming traditional agricultural practices into a modern cash crop economy.

A Tripartite Relationship in the Cotton Economy

At the heart of this cultural exchange lay the cotton industry—a sector dominated by Indian merchants, cultivated by African farmers, and regulated by European colonial administrators. Each group brought distinct perspectives, skills, and motivations to the table, resulting in a complex interplay of interests.

- Indian Merchants as Economic Catalysts

Indian traders emerged as key intermediaries in the cotton supply chain, bridging the gap between African growers and global markets. Their willingness to venture deep into rural areas—despite risks such as disease, lack of infrastructure, and cultural barriers—demonstrated an entrepreneurial spirit that left an indelible mark on Ugandan society. By establishing ginneries closer to growing regions, they reduced logistical challenges for African farmers and stimulated production.Beyond their economic contributions, Indian merchants introduced new technologies and business practices that influenced local communities. For example, the double sowing system adopted in Teso district likely stemmed from interactions with Indian traders who encouraged innovative methods to maximise yields. Such exchanges fostered a degree of mutual respect, as Africans came to rely on Indians for access to markets and technical expertise.

- African Farmers as Pillars of Production

African farmers formed the backbone of the cotton industry, supplying raw materials through their labour-intensive cultivation efforts. Initially hesitant to adopt cash crop agriculture, many Basoga were inspired by the example set by educated chiefs and Indian entrepreneurs. Chiefs, educated at prestigious institutions like Mengo High School and King’s College, Budo, served as intermediaries, translating colonial directives into actionable steps for their communities.Over time, African growers adapted their farming techniques based on interactions with both Indians and Europeans. For instance, the Department of Agriculture promoted improved seed selection, soil preparation, and pest management strategies, often disseminated through Indian middlemen. This blending of indigenous knowledge with external innovations created a hybrid model of agriculture that balanced tradition with progress.

- European Administrators as Regulators and Innovators

European colonial officials viewed themselves as custodians of Uganda’s development, implementing policies designed to control and direct economic activity. While their paternalistic approach sometimes alienated African and Indian stakeholders, it also led to significant infrastructural investments, such as roads and railways, which facilitated trade. The construction of the Mombasa-Tororo-Mbulamuti railway, for example, connected remote regions like Busoga to larger markets, benefiting all parties involved.However, European regulation was not without controversy. Policies like the Uganda Cotton Rules of 1918 and the Five-Mile Radius Policy of 1919 sought to curb Indian dominance in the cotton trade, favouring smaller European-owned ginneries over larger Indian operations. These measures created tensions but also spurred dialogue between the groups, highlighting the interconnectedness of their fates.

Cultural Adaptation and Mutual Influence

The interactions between Indians, Africans, and Europeans extended beyond economics, fostering a rich tapestry of cultural adaptation and mutual influence.

- Language and Communication

Language became a crucial tool for bridging cultural divides. Many Indian merchants learned local dialects to better communicate with African farmers, while some Africans picked up rudimentary Gujarati or Hindi phrases to facilitate trade. English, imposed as the language of administration, further unified these diverse groups under a common linguistic framework. This multilingual environment underscored the fluidity of cultural boundaries and the shared goal of economic prosperity. - Social Practices and Traditions

Social practices evolved as a result of sustained contact. Indian merchants often participated in community gatherings, offering small gifts or hosting meals to build goodwill among African growers. Similarly, African customs, such as drumming rhythms like SsagaZa agalamidde (“morning sleepers wake up and work”), found resonance even among non-African participants. These gestures of inclusion helped forge bonds across cultural lines. - Religious and Educational Exchanges

Religious beliefs and educational initiatives also played a role in shaping the socio-economic dynamic. Christian missionaries, aligned with colonial authorities, established schools that educated future leaders like Yosia Madiope and Ezekieri Wako. These institutions attracted students from diverse backgrounds, promoting cross-cultural understanding. Meanwhile, Hindu festivals celebrated by Indian communities occasionally drew interest from African neighbours, creating opportunities for shared experiences.

Tensions and Resolutions

Despite the collaborative aspects of this cultural exchange, tensions inevitably arose due to competing interests and perceptions of exploitation.

- Perceived Exploitation

Some African growers accused Indian traders of paying unfairly low prices for raw cotton and charging exorbitant fees for ginning services. Similarly, European administrators viewed Indian dominance in the cotton trade with suspicion, fearing its impact on Lancashire mills. These grievances highlighted the power imbalances inherent in the tripartite relationship. - Protests and Negotiations

In response to restrictive policies like the Five-Mile Radius Rule, Indian merchants formed organisations such as the Free Traders’ Union of Uganda to advocate for fairer treatment. African peasants, alarmed by the formation of exclusive European syndicates, joined protective organisations to safeguard their livelihoods. These collective actions underscored the resilience of marginalized groups and their ability to negotiate change within the system. - Shared Prosperity

Despite the challenges, evidence of shared prosperity surfaced during the 1920s. Increased cotton exports to India and Japan enriched Indian merchants, enabling them to diversify into industries like sugar manufacturing. African growers benefited from higher incomes, allowing some to afford luxuries previously unimaginable. Even European administrators reaped rewards through increased tax revenues and enhanced infrastructure.

Legacy of Cultural Exchange

The legacy of these interactions endures as a testament to the transformative power of cultural exchange. By working together—albeit imperfectly—Indians, Africans, and Europeans laid the foundations for Uganda’s modern economy. Their efforts not only diversified agricultural output but also introduced industrial practices that continue to shape the nation today.

Ultimately, the story of cultural exchange in colonial Uganda serves as a reminder of what can be achieved when individuals from different backgrounds collaborate towards a common goal. It highlights the complexities of human relationships, demonstrating how cooperation and conflict coexist in the pursuit of progress. As Uganda continues to navigate its path toward sustainable development, the lessons imparted by this unique socio-economic dynamic remain as relevant now as they were a century ago.

- Indian Merchants as Economic Catalysts

Legislative Challenges

Cotton Rules of 1918: Detailing the Restrictive Measures Imposed by the British Government Aimed at Excluding Indians from the Trade

The Cotton Rules of 1918 , enacted by the British colonial government in Uganda, marked a turning point in the dynamics of the cotton industry. These rules were explicitly designed to curb the growing influence of Indian merchants in the cotton trade, which had expanded significantly during and after the First World War. By introducing a series of restrictive measures, the colonial administration sought to protect European interests—particularly those aligned with Lancashire’s textile mills—while sidelining Indian traders who had become dominant players in the industry. This move not only reshaped the economic landscape of Uganda but also deepened racial and economic divisions within the colony.

Background: The Rise of Indian Merchants

By the end of the First World War, Indian merchants had established themselves as indispensable intermediaries in Uganda’s cotton supply chain. They ventured into remote areas, often at great personal risk, to purchase raw cotton directly from African growers. Their entrepreneurial spirit led to the establishment of ginneries near key growing regions, such as Jinja and Kampala, which streamlined processing and reduced logistical barriers for farmers. Furthermore, Indian traders played a pivotal role in popularising Ugandan cotton in Indian mills, particularly in Bombay, where it was valued for spinning finer fibres.

This dominance alarmed both colonial officials and European competitors, who viewed Indian participation in the cotton trade as a threat to their own economic interests. For Lancashire mill owners, the increasing export of long-staple Ugandan cotton to India posed a dual challenge: it raised prices on the global market and enabled Indian manufacturers to produce high-quality textiles that could compete with British goods. To counteract these developments, the British government introduced the Cotton Rules of 1918—a legislative framework aimed squarely at excluding Indians from the trade.

Key Provisions of the Cotton Rules

The Cotton Rules of 1918 imposed several stringent regulations that disproportionately affected Indian merchants:

- Licensing Requirements for Buying Cotton

Under the new rules, anyone wishing to buy unginned cotton required a licence issued by district commissioners. While this measure ostensibly aimed to regulate the industry, its implementation was heavily biased against Indian traders. District commissioners were given discretionary powers to deny licences based on vague criteria, effectively allowing them to exclude individuals or groups deemed undesirable. In practice, many Indian merchants found it exceedingly difficult to secure licences, while European traders faced fewer obstacles. - Five-Mile Radius Policy

One of the most controversial aspects of the Cotton Rules was the introduction of the “five-mile radius” policy. This regulation prohibited the issuance of buying licences within a five-mile radius of existing ginneries. Ostensibly framed as a public health measure under the guise of preventing the spread of disease through cotton seeds, the rule had no scientific basis. In reality, it served to grant artificial protection to smaller European-owned ginneries located in interior districts, while cutting off supplies to larger Indian-owned facilities concentrated at ports like Jinja and Kampala. This policy severely disadvantaged Indian merchants, whose operations relied on bulk purchases transported over long distances. - Restrictions on Ginneries

The rules also tightened controls on the establishment and operation of ginneries. Licences for setting up new ginneries were subject to approval by colonial authorities, who prioritised applications from European enterprises. Indian-owned ginneries, which accounted for nearly 90% of the industrial output in Uganda by the early 1920s, were systematically marginalised. For instance, the Narandas Rajram & Co., a prominent Bombay-based firm, suffered significant losses due to the application of these rules. - Transport Restrictions

Another discriminatory provision involved restrictions on the transportation of seed cotton. While land transport remained largely unaffected, movement of cotton via Lake Victoria Nyanza was banned under the pretext of medical concerns. This selective enforcement disproportionately impacted Indian traders, who frequently used waterways to transport large quantities of cotton efficiently. Meanwhile, European competitors continued to benefit from less restrictive land routes.

Impact on Indian Traders

The Cotton Rules of 1918 dealt a severe blow to Indian merchants, who had invested heavily in the cotton industry. Key impacts included:

- Loss of Market Access: The five-mile radius policy and licensing restrictions effectively barred Indian traders from accessing raw cotton in many growing regions. Without reliable sources of supply, their ability to compete in the market dwindled rapidly.

- Decline in Gin Ownership: Between 1920 and 1927, the number of Indian-owned ginneries plummeted despite an overall increase in the total number of facilities. By 1927, Indians owned just 125 out of 189 ginneries, down from 32 out of 119 in 1920. This decline reflected the systematic exclusion of Indian entrepreneurs from the industry.

- Economic Hardship: Many Indian traders faced financial ruin as a result of the new regulations. Those who survived were forced to adapt by diversifying into other sectors, such as sugar manufacturing, or by operating as agents for European firms.

Broader Implications

The Cotton Rules of 1918 underscored the colonial government’s willingness to intervene in the economy to protect vested European interests. However, the consequences extended beyond the immediate targeting of Indian merchants:

- Disruption for African Growers: African peasants, who depended on Indian buyers for access to markets, were adversely affected by the sudden reduction in competition. With fewer options for selling their cotton, they often received lower prices for their produce.

- Rise of Protective Organizations: The formation of exclusive European syndicates, such as the Buganda Seed Cotton Buying & Ginning Association in 1928, further exacerbated tensions. In response, Indian middlemen founded the Free Traders’ Union of Uganda to advocate for fairer treatment. Similarly, protective organisations sprang up among African growers, reflecting widespread dissatisfaction with the changes.

- Calls for Reform: The contentious nature of the Cotton Rules prompted calls for reform. In 1929, the Uganda Prices Enquiry Commission was appointed to investigate issues related to cotton pricing and marketing. While the commission acknowledged the adverse effects of European combines on growers, it stopped short of reversing the policies that disadvantaged Indian traders.

Legitimacy and Criticism

Critics argued that the Cotton Rules lacked legitimacy, pointing out the flimsy justification for measures like the five-mile radius policy. Nowhere else in the world was cotton seed treated as a special carrier of disease, raising suspicions about the true motives behind the legislation. Moreover, the blatant favouritism shown towards European traders highlighted the racial bias inherent in colonial governance.

- Licensing Requirements for Buying Cotton

Indian merchants lodged numerous protests, submitting memoranda and petitions to colonial authorities. They contended that the rules harmed their businesses and undermined the broader economic development of Uganda. Despite their efforts, however, the colonial government remained steadfast in its commitment to protecting European interests.

Legacy of the Cotton Rules

The Cotton Rules of 1918 left an indelible mark on Uganda’s economic history. By excluding Indian merchants from the cotton trade, the British government altered the trajectory of industrial growth in the colony. While the rules succeeded in bolstering European enterprises in the short term, they sowed the seeds of discontent among both Indian traders and African growers. This discontent would later manifest in organised resistance and demands for greater economic inclusion.

Ultimately, the Cotton Rules exemplify how colonial policies were often shaped by external pressures—such as the lobbying efforts of Lancashire mill owners—and prioritised imperial interests over local needs. As Uganda continues to grapple with questions of equity and opportunity in its modern economy, the legacy of these restrictive measures serves as a reminder of the enduring impact of historical injustices.

Five-Mile Radius Policy: Examining the Impact of Licensing Restrictions on Indian-Owned Ginneries Versus European-Controlled Operations

The Five-Mile Radius Policy , introduced as part of the Cotton Rules of 1918 in Uganda, stands as one of the most contentious and discriminatory measures imposed by the British colonial government. This policy prohibited the issuance of buying licenses within a five-mile radius of existing ginneries, ostensibly framed as a public health measure to prevent the spread of disease through cotton seeds. However, its true intent was far more insidious: it sought to grant artificial protection to smaller European-owned ginneries located in interior districts while severely disadvantaging larger Indian-owned facilities concentrated at ports like Jinja and Kampala. By examining the impact of this policy on Indian-owned ginneries versus European-controlled operations, we uncover a tale of economic manipulation, racial bias, and systemic exclusion that reshaped Uganda’s cotton industry.

Origins and Justification of the Five-Mile Radius Policy

The Five-Mile Radius Policy emerged during a period when Indian merchants had established themselves as dominant players in Uganda’s cotton trade. Through their entrepreneurial efforts, they had built an extensive network of ginneries near key growing regions, enabling them to purchase raw cotton directly from African growers. Their proximity to major transportation hubs such as Lake Victoria further solidified their competitive advantage.

European competitors, however, struggled to match the efficiency and scale of Indian operations. Many European-owned ginneries were smaller and scattered across remote areas, making them less accessible to growers. To counteract this disparity, colonial authorities devised the Five-Mile Radius Policy. Under the guise of medical concerns—claiming that seed cotton carried diseases—the rule effectively barred Indian traders from accessing raw cotton supplies near existing ginneries. This selective enforcement disproportionately impacted Indian merchants, who relied on bulk purchases transported over long distances.

Impact on Indian-Owned Ginneries

The Five-Mile Radius Policy dealt a severe blow to Indian-owned ginneries, which accounted for nearly 90% of Uganda’s industrial output by the early 1920s. Key impacts included:

- Loss of Supply Chains

The policy cut off critical supply lines for Indian ginneries, particularly those clustered at ports like Jinja and Kampala. Without access to raw cotton from nearby growing regions, these facilities faced significant operational challenges. For example, the Bombay-based firm Narandas Rajram & Co. suffered substantial losses due to the application of the Five-Mile Radius Rule, as it could no longer secure sufficient quantities of seed cotton to sustain its operations. - Decline in Ownership

Between 1920 and 1927, the number of Indian-owned ginneries plummeted despite an overall increase in the total number of facilities. In 1920, Indians owned 32 out of 119 ginneries ; by 1927, this figure had dropped to just 125 out of 189 . This decline reflected the systematic marginalization of Indian entrepreneurs, who found themselves increasingly excluded from the industry they had helped build. - Economic Hardship

Many Indian traders faced financial ruin as a result of the new regulations. Those who survived were forced to adapt by diversifying into other sectors, such as sugar manufacturing, or by operating as agents for European firms. For instance, Nanjibhai K. Mehta , once a prominent cotton trader, shifted his focus to establishing the Lugazi Sugar Works in 1923 after being squeezed out of the cotton market. - Disruption of Transport Networks

The prohibition on transporting seed cotton via Lake Victoria Nyanza further exacerbated the plight of Indian merchants. While land transport remained largely unaffected, waterways had been a vital means of efficiently moving large quantities of cotton. By restricting this mode of transport, the colonial government effectively curtailed one of the primary logistical advantages enjoyed by Indian traders.

Advantages for European-Controlled Operations

In stark contrast to the hardships faced by Indian merchants, the Five-Mile Radius Policy provided significant benefits to European-controlled operations:

- Artificial Protection

Smaller European-owned ginneries in interior districts gained a virtual monopoly over local cotton supplies. With Indian buyers barred from competing within the designated radius, these facilities enjoyed guaranteed access to raw materials, even if their efficiency and capacity paled in comparison to Indian counterparts. - Increased Market Share

The policy enabled European ginners to consolidate their position in the market. For example, the formation of exclusive associations like the Buganda Seed Cotton Buying & Ginning Association in 1928 further entrenched European dominance by allowing members to buy cotton directly from growers and process it in their own ginneries. Such arrangements effectively excluded Indian middlemen from participating in the trade. - Strategic Placement

European ginneries were often strategically located near rural communities, ensuring easy access to growers. Combined with the protections afforded by the Five-Mile Radius Policy, this placement gave European operators a decisive edge over Indian rivals, whose facilities were typically farther away.

Broader Implications

The Five-Mile Radius Policy not only altered the competitive landscape of Uganda’s cotton industry but also had profound socio-economic consequences:

- Disruption for African Growers

African peasants, who depended on Indian buyers for access to markets, were adversely affected by the sudden reduction in competition. With fewer options for selling their cotton, they often received lower prices for their produce. The policy thus undermined the very growers it purported to protect. - Rise of Protective Organizations

The formation of exclusive European syndicates sparked widespread discontent among African growers and Indian traders alike. In response, protective organizations sprang up across Buganda and Busoga, reflecting a growing sense of alarm over the direction of the industry. Indian middlemen, meanwhile, founded the Free Traders’ Union of Uganda in 1928 to advocate for fairer treatment and demand reforms. - Calls for Reform

The contentious nature of the Five-Mile Radius Policy prompted calls for reform. In 1929, the Uganda Prices Enquiry Commission was appointed to investigate issues related to cotton pricing and marketing. While the commission acknowledged the adverse effects of European combines on growers, it stopped short of reversing the policies that disadvantaged Indian traders.

Criticism and Legitimacy

Critics argued that the Five-Mile Radius Policy lacked legitimacy, pointing out the flimsy justification for treating cotton seed as a special carrier of disease. Nowhere else in the world was such a claim made, raising suspicions about the true motives behind the legislation. Moreover, the blatant favoritism shown towards European traders highlighted the racial bias inherent in colonial governance.

Indian merchants lodged numerous protests, submitting memoranda and petitions to colonial authorities. They contended that the rules harmed their businesses and undermined the broader economic development of Uganda. Despite their efforts, however, the colonial government remained steadfast in its commitment to protecting European interests.

Legacy of the Five-Mile Radius Policy

The Five-Mile Radius Policy left an indelible mark on Uganda’s economic history. By excluding Indian merchants from the cotton trade, the British government altered the trajectory of industrial growth in the colony. While the policy succeeded in bolstering European enterprises in the short term, it sowed the seeds of discontent among both Indian traders and African growers. This discontent would later manifest in organized resistance and demands for greater economic inclusion.

Ultimately, the Five-Mile Radius Policy exemplifies how colonial policies were often shaped by external pressures—such as the lobbying efforts of Lancashire mill owners—and prioritized imperial interests over local needs. As Uganda continues to grapple with questions of equity and opportunity in its modern economy, the legacy of these restrictive measures serves as a reminder of the enduring impact of historical injustices.

- Loss of Supply Chains

Medical Grounds Debate: Questioning the Validity of Using Health Ordinances to Justify Discriminatory Practices Against Indian Traders

The use of health ordinances, particularly under the guise of preventing disease, to justify discriminatory practices against Indian traders in Uganda remain one of the most contentious aspects of colonial-era cotton legislation. The Five-Mile Radius Policy and other restrictive measures introduced in 1918–1919 were ostensibly framed as public health interventions aimed at curbing the spread of diseases through cotton seeds. However, a closer examination reveals that these policies lacked scientific merit and were instead designed to serve broader economic and racial agendas. By scrutinising the validity of such justifications, we uncover a narrative rife with ulterior motives, systemic bias, and profound implications for Uganda’s socio-economic development.

The Pretence of Medical Necessity

The cornerstone of the British government’s argument was the claim that cotton seeds posed a significant health risk, warranting stringent controls on their transportation and trade. For instance, the Prevention of Diseases Ordinance of February 1919 explicitly prohibited the transport of seed cotton via Lake Victoria Nyanza, while allowing unrestricted movement by land or across smaller lakes like Lake Kioga. This selective enforcement raised immediate suspicions about the true intent behind the regulation.

Critics have long argued that there was no credible evidence to support the notion that cotton seeds were carriers of disease. Nowhere else in the world—at least not during this period—was cotton seed treated as a vector for illness. The absence of any documented outbreaks linked to seed cotton further undermines the legitimacy of such claims. Indeed, the policy appears less concerned with public health and more focused on curtailing the activities of Indian merchants who had become dominant players in the cotton trade.

Disproportionate Impact on Indian Traders

If the purported aim of the health ordinances was genuinely to safeguard public welfare, one would expect their implementation to be impartial and universally applied. Instead, the regulations disproportionately targeted Indian traders, whose operations were concentrated near ports like Jinja and Kampala. By banning the issuance of buying licences within a five-mile radius of existing ginneries, the colonial government effectively deprived Indian-owned facilities of access to raw cotton supplies.

For example, firms like Narandas Rajram & Co. , a prominent Bombay-based enterprise, suffered significant losses due to the application of these rules. Similarly, successful entrepreneurs like Nanjibhai K. Mehta and Muljibhai P. Madvani , who had invested heavily in ginning infrastructure, found themselves squeezed out of the market. Meanwhile, European-controlled ginneries in interior districts benefited from artificial protection, gaining virtual monopolies over local cotton supplies.