Uganda Under Colonial Rule: How Imposed Systems Shaped a Nation’s Future

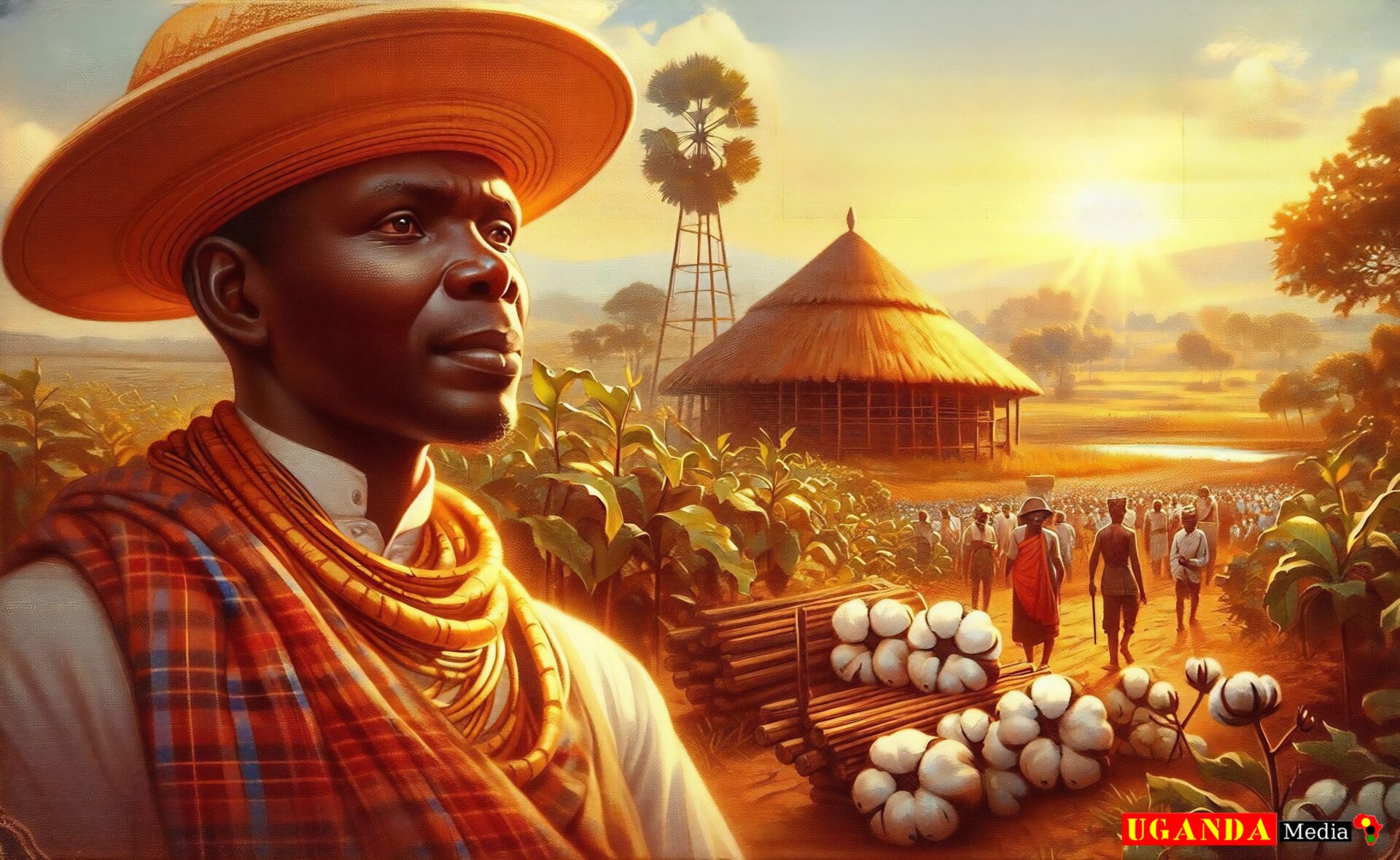

The colonial era in Uganda was marked by profound transformations in governance, land ownership, and social structures, driven by British administrators and their imposition of foreign systems. From the artificial creation of chieftaincies in acephalous societies like Lango and Teso to the coercive alienation of land under the mailo system in Buganda, these policies reshaped the fabric of Ugandan society. While some appointed chiefs skilfully navigated their roles to advocate for local interests, others became instruments of exploitation, exacerbating tensions between colonial authorities and rural populations. This legacy of imposed hierarchies, economic disparities, and fractured traditions continues to influence post-independence governance in Uganda. By examining the interplay of resistance, adaptation, and compromise during this period, we gain critical insights into the enduring impact of colonialism and the path toward fostering inclusive, equitable systems rooted in justice and cultural heritage.

This article delves into the complex interplay between British administrators and colonial chiefs during Uganda’s colonial era. Through real-world examples, scholarly insights, and a compelling narrative, we’ll explore how power was negotiated, resisted, and redefined within the framework of empire. By the end, readers will not only grasp the historical significance of these interactions but also reflect on their enduring legacies.

Introduction to Indirect Rule: The Cornerstone of British Colonial Policy in Uganda

In the annals of colonial history, few administrative strategies have left as indelible a mark as indirect rule , a policy that became synonymous with British governance across its African colonies. Rooted in pragmatism and a desire to govern vast territories with minimal resources, indirect rule sought to maintain imperial control by co-opting local power structures—or creating them where they did not exist. In Uganda, this approach was both a reflection of British conservatism and an adaptation to the country’s diverse political landscapes, which ranged from highly centralised kingdoms like Buganda to acephalous societies in regions such as Lango and Teso.

The Concept of Indirect Rule

At its core, indirect rule was predicated on the belief that traditional authority structures were inherently hierarchical and organic—a notion deeply embedded in conservative British thought. As articulated by figures like Lord Lugard, one of the architects of the policy, indirect rule relied on the premise that Africans could be governed through their own “tribal” institutions, mediated by appointed or recognised chiefs who would act as intermediaries between the colonial state and the governed populace. This method was considered cost-effective, culturally sensitive (at least superficially), and conducive to maintaining order without overextending British manpower.

However, beneath this veneer of respect for tradition lay a more utilitarian reality. Indirect rule was less about preserving authentic African customs than it was about consolidating colonial control. It allowed the British to project authority while minimising direct involvement in day-to-day administration. Chiefs were often transformed into bureaucratic agents of the colonial regime, wielding powers far beyond those traditionally accorded to leaders in many Ugandan societies.

Implementation in Uganda: A Patchwork Approach

Uganda presented a unique challenge for British administrators due to its remarkable diversity. Precolonial Uganda was not a unified entity but rather a mosaic of distinct polities, each with its own social, political, and economic systems. The British response was to adopt a patchwork approach, tailoring their implementation of indirect rule to fit the idiosyncrasies of different regions.

- Buganda: The Model for Indirect Rule

The kingdom of Buganda, with its sophisticated system of governance, provided the blueprint for indirect rule in Uganda. Here, the British found a ready-made hierarchy led by the Kabaka (king) and his council of chiefs. Under the 1900 Buganda Agreement, the British formalised this arrangement, granting Buganda a degree of autonomy under the Kabaka’s leadership. This model proved so successful from the colonial perspective that it was later exported—with varying degrees of success—to other parts of the protectorate. - Lango: Resistance to Imposed Authority

In stark contrast to Buganda, the Lango people operated within small-scale, egalitarian clan-based systems that lacked hereditary leadership. When British officials attempted to impose chiefly authority upon these communities, they encountered significant resistance. Chiefs appointed by the colonial administration were viewed as artificial constructs, alien to Lango conceptions of political order. Over time, however, some appointees learned to manipulate their positions, blurring the lines between imposed roles and perceived legitimacy. - Teso: A Hybrid System

The case of Teso illustrates how indirect rule could take on hybrid forms depending on historical context. Conquered initially by General Kakunguru, a Baganda military leader acting on behalf of the British, Teso saw the imposition of Ganda administrators alongside locally appointed chiefs. Yet, even here, the precolonial absence of institutionalised chieftaincies meant that the new structures bore little resemblance to indigenous traditions. Instead, they reflected the exigencies of colonial conquest and administration.

Challenges and Contradictions

While indirect rule promised stability and efficiency, its implementation revealed deep contradictions. British administrators frequently misunderstood—or wilfully misrepresented—the societies they sought to govern. For instance, the stereotype of the “authoritative tribal chief” clashed with the realities of acephalous societies, where leadership was fluid and contingent upon specific circumstances. Moreover, the imposition of foreign models created tensions between appointed chiefs and the communities they were meant to represent. Peasants subjected to extortionate labour demands and arbitrary exercise of chiefly power often harboured resentment towards these colonial creations.

Despite these challenges, indirect rule persisted because it aligned with the ideological framework of British conservatism. Change, in this worldview, was best achieved organically, building upon existing institutions rather than imposing radical reforms. Thus, even when evidence suggested that certain practices were incongruous with local customs, administrators clung to their assumptions, reducing cognitive dissonance by reinterpreting reality to fit their preconceived notions.

Conclusion

Indirect rule remains a defining feature of Uganda’s colonial legacy, shaping post-independence governance and societal dynamics. Its introduction reflected both the adaptability and the limitations of British colonial policy, revealing how global ideologies were refracted through local contexts. From the fertile plains of Buganda to the arid expanses of Teso, the story of indirect rule is one of negotiation, resistance, and transformation—a precursor to the complex nation-building process that continues to unfold in modern-day Uganda.

- Buganda: The Model for Indirect Rule

The Buganda Model: How the Centralised Political Structure of Buganda Influenced British Administrative Strategies Elsewhere in Uganda

In the colonial history of Uganda, few regions left as profound an imprint on British governance strategies as Buganda. The kingdom of Buganda, with its sophisticated and centralised political structure, served as a template for British administrative policies not only within its borders but also across other parts of the protectorate. This influence stemmed from both the practical utility of Buganda’s hierarchical system and the ideological resonance it held with British conservative thought. By examining how the Buganda model shaped British strategies elsewhere in Uganda, we gain insight into the broader dynamics of colonial rule and the tensions that arose when foreign systems were imposed upon diverse societies.

The Foundations of the Buganda Model

Buganda was unique among precolonial Ugandan polities in its highly structured monarchy, led by the Kabaka (king), who wielded significant authority over a network of appointed chiefs (batongole ) and clan leaders. This centralised system contrasted sharply with the more egalitarian or acephalous societies found in regions like Lango, Teso, and Acholi. For British administrators arriving in Uganda at the turn of the 20th century, Buganda represented an idealised vision of African governance—one that aligned neatly with their conservative worldview, which celebrated hierarchy, tradition, and organic social order.

The 1900 Buganda Agreement formalised this arrangement, granting Buganda a degree of autonomy under the Kabaka while ensuring cooperation with British interests. Chiefs appointed by the colonial administration were integrated into this framework, effectively becoming bureaucratic agents tasked with collecting taxes, enforcing laws, and mediating between the colonial state and local populations. This dual role—bridging indigenous custom and imperial control—made the Buganda model particularly appealing to British officials seeking efficient ways to govern vast territories with limited resources.

Exporting the Buganda Model Across Uganda

While the Buganda system worked relatively smoothly within the kingdom itself, replicating it elsewhere proved far more challenging. British administrators, however, remained undeterred, convinced that indirect rule through “traditional” authorities could be adapted to any context. This belief reflected not only pragmatic considerations but also deep-seated assumptions about African societies—that they were inherently hierarchical and amenable to governance through tribal leadership.

- Imposition in Lango

In Lango, where small-scale clan-based systems prevailed, the imposition of chiefly authority was met with resistance. Precolonial Lango society lacked hereditary leadership; decisions were made collectively by elders, and power was dispersed rather than concentrated. When British officials introduced appointed chiefs, they fundamentally altered existing structures, creating positions of authority that were alien to Lango conceptions of political order. Over time, some appointees learned to exploit their roles, blurring the distinction between traditional legitimacy and colonial fiat. Nevertheless, the disjuncture between imposed structures and indigenous realities persisted, leading to resentment among peasants subjected to extortionate labour demands and arbitrary exercise of chiefly power. - Hybrid Systems in Teso

The case of Teso illustrates how the Buganda model was adapted to fit local conditions. Initially conquered by General Kakunguru, a Baganda military leader acting on behalf of the British, Teso saw the establishment of a hybrid administrative structure. Ganda administrators oversaw local men appointed as chiefs, blending elements of Buganda’s hierarchical model with precolonial traditions. However, even here, the absence of institutionalised chieftaincies meant that the new structures bore little resemblance to indigenous customs. Instead, they reflected the exigencies of colonial conquest and administration. - Variations Across Regions

Vincent (1982) highlights how ecological and demographic factors influenced the adaptability of the Buganda model. In areas closer to caravan routes used by traders, such as parts of southern Teso, there was a tendency towards consolidation of leadership, making it easier to impose hierarchical structures. In contrast, northern regions experienced a decrease in political scale during the late 19th century, complicating efforts to establish cohesive administrative units. These variations underscored the challenges of applying a one-size-fits-all approach to governance.

Ideological Resonance and Cognitive Dissonance

The appeal of the Buganda model lay not only in its practicality but also in its alignment with British conservative ideology. As Tosh (1978) notes, many British officials came to view their appointed chiefs as embodying traditional legitimacy, despite evidence to the contrary. This perception allowed administrators to reconcile their commitment to indirect rule with the artificial nature of many colonial creations. Over time, district officers began to assume that chiefs were traditional authorities who should be disturbed as little as possible, reinforcing the illusion of continuity between precolonial and colonial systems.

However, this cognitive dissonance—the tension between observed reality and ingrained assumptions—was difficult to sustain. Reflective administrators, aware of the historical facts, often coped by adding consonant elements to their beliefs. For instance, they argued that appointed chiefs, though lacking true traditional status, were nonetheless representative of local communities. This notion of representativity, however, was deeply flawed, as it ignored the lack of institutional mechanisms for accountability. Chiefs were salaried bureaucratic appointees, simultaneously tax collectors and enforcers of colonial edicts—a far cry from the organic leaders envisioned by British conservatives.

Legacy and Lessons

The influence of the Buganda model extended beyond the colonial period, shaping post-independence governance in Uganda. Its legacy is evident in the persistence of hierarchical structures and the continued reliance on appointed intermediaries to manage relations between the state and local populations. At the same time, the contradictions inherent in the model highlight the dangers of imposing foreign systems without regard for indigenous contexts.

For contemporary policymakers, the story of the Buganda model offers valuable lessons. It underscores the importance of recognising diversity and fostering inclusive governance structures that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. While the British may have viewed Buganda as a blueprint for success, their attempts to replicate it elsewhere reveal the complexities and unintended consequences of top-down reforms.

In sum, the Buganda model exemplifies both the ingenuity and the limitations of British colonial policy in Uganda. By leveraging Buganda’s centralised system, administrators sought to extend their reach across the protectorate, often with mixed results. Understanding these dynamics provides crucial insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for equitable governance in modern-day Uganda.

- Imposition in Lango

Lango Resistance to Chiefly Authority: Highlighting How Lango Society, Which Lacked Hereditary Leadership, Struggled Against Imposed Chieftaincies

In the colonial history of Uganda, few regions exemplify the tensions between indigenous social structures and externally imposed governance as vividly as Lango. The Lango people, whose society was rooted in small-scale, egalitarian clan-based systems, found themselves at odds with British attempts to impose hierarchical chiefly authority—a structure entirely alien to their way of life. This resistance highlights not only the cultural dissonance between colonial administrators and local communities but also the broader challenges inherent in applying a one-size-fits-all model of indirect rule across Uganda’s diverse polities.

The Nature of Precolonial Lango Society

Precolonial Lango society operated without institutionalised hereditary leadership or centralised political structures. Power and decision-making were dispersed among clan elders, who collectively deliberated on matters affecting their communities. Leadership roles were fluid, emerging temporarily during times of crisis or need, such as war, and dissolving once the situation resolved. Ritual leaders and age-set systems further contributed to the organisation of social and military activities, though these too lacked permanence or coercive power.

This decentralised system stood in stark contrast to the hierarchical models favoured by British administrators, who viewed African societies through the lens of conservative ideology. To them, order and stability could only be achieved through clearly defined chains of command led by authoritative figures akin to tribal chiefs. In the absence of such structures in Lango, British officials took it upon themselves to create them, appointing individuals as “chiefs” to serve as intermediaries between the colonial state and the governed populace.

The Imposition of Chiefly Authority

The introduction of appointed chieftaincies into Lango society was met with significant resistance. For the Langi, these positions of authority were not merely unfamiliar—they were fundamentally incompatible with their conceptions of political order. Chiefs, in the colonial sense, wielded powers that far exceeded anything traditionally accorded to leaders within Lango society. They acted as tax collectors, enforcers of colonial edicts, and arbiters of disputes, often using their newfound authority to extract resources and labour from peasants under coercive conditions.

As Tosh (1978) notes, the imposition of chiefly authority radically transformed both the qualitative and quantitative dimensions of leadership in Lango. Appointed chiefs became conduits of colonial power, wielding influence that was qualitatively different from the consensual and context-specific leadership of precolonial times. This transformation disrupted existing social dynamics, creating resentment among those subjected to arbitrary exercises of power.

Strategies of Resistance

Resistance to imposed chieftaincies manifested in various forms, ranging from passive non-compliance to more overt acts of defiance. Peasants, burdened by extortionate labour demands and exploitative practices, expressed their discontent through refusal to cooperate with colonial directives enforced by appointed chiefs. Clan elders, whose traditional roles had been undermined by the new structures, sometimes sought to reclaim their influence by challenging the legitimacy of these foreign-imposed leaders.

Over time, however, some appointed chiefs learned to manipulate the system to their advantage. By leveraging their familiarity with British expectations and exploiting loopholes in colonial oversight, they consolidated their positions and even passed them down to their sons. Tosh (1978: 189-90) documents instances where hereditary succession began to blur the distinction between the British stereotype of an African tribal chief and the reality of Lango’s imposed chieftaincies. While this adaptation may have provided short-term stability for certain individuals, it did little to address the underlying grievances of the broader population.

Changing Perceptions Among British Officials

The struggle against imposed chieftaincies in Lango also reveals shifting perceptions among British officials over time. Initially, administrators conflated the egalitarian leaders of small clan sections with their own stereotypes of authoritative tribal chiefs. However, experience soon exposed the inadequacy of this assumption. As noted by Tosh (1978: 245), district officers in the 1920s and early 1930s began to regard appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy, despite evidence to the contrary. This belief allowed them to justify granting greater latitude to their appointees, reinforcing the illusion of continuity between precolonial and colonial systems.

Yet, cognitive dissonance—the tension between observed reality and ingrained assumptions—remained a persistent challenge for reflective administrators. Some officials, aware of the artificial nature of many colonial creations, coped by adding consonant elements to their beliefs. For example, they argued that appointed chiefs, though lacking true traditional status, were nonetheless representative of local communities. This notion of representativity, however, was deeply flawed, as it ignored the lack of institutional mechanisms for accountability. Chiefs were salaried bureaucratic appointees, simultaneously tax collectors and enforcers of colonial edicts—a far cry from the organic leaders envisioned by British conservatives.

Legacy and Lessons

The legacy of imposed chieftaincies in Lango extends beyond the colonial period, shaping post-independence governance and societal dynamics. The contradictions inherent in the system highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts. For contemporary policymakers, the story of Lango offers valuable lessons about the importance of recognising diversity and fostering inclusive governance structures that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities.

In sum, the resistance to chiefly authority in Lango underscores the complexities and unintended consequences of top-down reforms. While British administrators may have viewed their efforts as pragmatic solutions to administrative challenges, their actions sowed seeds of discontent that continue to resonate in modern-day Uganda. Understanding these dynamics provides crucial insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for equitable governance.

Hereditary vs. Appointed Chiefs: Analysing the Blurring Line Between Traditional Inheritance and Colonial Appointments, Citing Tosh (1978)

In the colonial history of Uganda, one of the most striking transformations brought about by British rule was the redefinition of leadership structures, particularly through the introduction of appointed chiefs. This shift created a complex and often ambiguous relationship between traditional systems of hereditary inheritance and the artificial hierarchies imposed by colonial administrators. John Tosh’s seminal work, Clan Leaders and Colonial Chiefs in Lango (1978), provides critical insights into how these two forms of authority intersected, overlapped, and ultimately blurred over time, leaving a lasting impact on Ugandan society.

The Conceptual Divide: Hereditary Chiefs vs. Colonial Appointees

Precolonial Ugandan societies exhibited a wide variety of leadership structures, ranging from centralized monarchies like Buganda to acephalous or egalitarian systems such as those found in Lango and Teso. In regions with hereditary leadership, positions of authority were passed down within families, often accompanied by rituals, ceremonies, and deep-rooted cultural legitimacy. These leaders derived their power not merely from coercion but from their roles as custodians of tradition, mediators of disputes, and symbols of communal identity.

In contrast, colonial-appointed chiefs were bureaucratic creations designed to serve as intermediaries between the colonial state and local populations. They lacked the organic connection to their communities that characterised traditional leaders. Instead, they were salaried officials tasked with enforcing colonial policies, collecting taxes, and maintaining order—roles that frequently placed them at odds with the people they ostensibly represented.

Despite these clear distinctions, British administrators often conflated the two categories, viewing all African leaders through the lens of their own conservative ideology. To them, hierarchical authority was natural and inevitable; thus, even in societies without hereditary chiefs, they sought to impose structures that mirrored what they understood as “tribal” leadership. This ideological predisposition laid the groundwork for the gradual blurring of lines between traditional inheritance and colonial appointments.

The Process of Blurring: Manipulation and Adaptation

Tosh (1978) documents how certain appointed chiefs skilfully manipulated the system to consolidate their positions and pass them down to their sons, mimicking the principle of hereditary succession. Over time, this practice created a semblance of continuity between colonial creations and precolonial traditions. For instance, in Lango—a region where leadership had historically been fluid and context-specific—appointed chiefs began to behave as though their roles were inherited rights rather than bureaucratic assignments. By the mid-20th century, some districts saw instances where the sons of appointed chiefs succeeded their fathers, further entrenching the illusion of hereditary legitimacy.

This phenomenon was not unique to Lango. Across Uganda, the distinction between appointed and hereditary chiefs became increasingly indistinct as colonial rule progressed. Tosh notes that district officers in the 1920s and early 1930s began to regard their appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy based on tribal custom. Speaking of this period, he writes: “District Officers—unlike their pre-war predecessors—were beginning to assume that the chiefs were traditional authorities who should be disturbed as little as possible” (Tosh, 1978: 245).

This perception allowed appointed chiefs to wield powers far beyond their original mandates, effectively transforming them into quasi-traditional figures. While this development may have provided short-term stability for the colonial administration, it also sowed seeds of resentment among ordinary peasants subjected to extortionate labour demands and arbitrary exercises of chiefly power.

Cognitive Dissonance Among Administrators

The blurring of lines between hereditary and appointed chiefs can also be understood through the lens of cognitive dissonance theory. British administrators, committed to the idea of building upon traditional institutions, faced a dilemma when confronted with evidence that many of their appointees lacked genuine indigenous legitimacy. According to Tosh, officials resolved this tension by altering their perceptions of reality. For example, they convinced themselves that appointed chiefs were representative of local communities, despite the absence of institutional mechanisms for accountability (Tosh, 1978: 247).

Reflective administrators, aware of the historical facts, coped differently. As Tosh suggests, these men added consonant elements to their beliefs, arguing that the British-imposed chiefly structure was eventually accepted as part of local tradition. This belief was especially effective in areas like Busoga, where Fallers (1965) found that the Soga people viewed the apparatus of client chiefs and local government as a legitimate continuation of precolonial states (cited in Tosh, 1978). However, in regions like Lango and Teso, where no such traditions existed, the claim rang hollow.

Legacy and Implications

The legacy of this blurring line between hereditary and appointed chiefs extends far beyond the colonial period. Post-independence governments in Uganda inherited administrative structures built around these hybrid figures, complicating efforts to forge inclusive governance models. The contradictions inherent in the system highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts.

For contemporary policymakers, the lessons are clear. Recognising diversity and fostering equitable governance requires moving away from rigid hierarchies and embracing participatory approaches that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. Understanding the dynamics of hereditary versus appointed leadership in colonial Uganda offers valuable insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for justice and representation in modern-day Africa.

In sum, the blurring line between traditional inheritance and colonial appointments underscores both the ingenuity and the limitations of British colonial policy in Uganda. While the imposition of chiefs served immediate administrative goals, it also reshaped social dynamics in ways that continue to resonate today. By examining these transformations through the lens of Tosh’s scholarship, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in a colonial setting.

Misconceptions About Tribal Leadership: Examining How British Officials Initially Confused Egalitarian Clan Leaders with Stereotypical “Authoritative Tribal Chiefs”

In the early days of British colonial rule in Uganda, one of the most persistent and consequential misconceptions was the assumption that all African societies were inherently hierarchical, governed by authoritative tribal chiefs akin to those found in Buganda. This belief, rooted in British conservative ideology and reinforced by stereotypes about “tribal” leadership, led officials to misinterpret egalitarian clan leaders as powerful, centralised figures. These misconceptions not only distorted colonial policies but also reshaped indigenous political systems in ways that left a lasting legacy on Ugandan society.

The British Stereotype of the “Authoritative Tribal Chief”

British administrators arrived in Uganda with preconceived notions about African governance, shaped by their own cultural and ideological frameworks. Conservative thought, which celebrated hierarchy and organic social order, predisposed them to view all African societies through the lens of hereditary authority. As noted by Tosh (1978), this perspective was deeply ingrained in the mindset of colonial officers, many of whom came from upper-middle-class backgrounds steeped in traditionalist values. To these men, the idea of an acephalous or egalitarian society was inconceivable—a contradiction that challenged their understanding of how human communities should function.

The stereotype of the “authoritative tribal chief” became a template for interpreting leadership across Uganda, regardless of local realities. In regions like Buganda, where a centralised monarchy existed, this model seemed to align neatly with British expectations. However, in other parts of the protectorate—such as Lango, Teso, and Acholi—the imposition of this stereotype created profound dissonance. Precolonial societies in these areas operated without institutionalised hereditary leadership; instead, power was dispersed among clan elders, ritual leaders, and temporary war leaders who emerged only during times of need. Yet, British officials failed to recognise—or chose to ignore—these distinctions, conflating fluid and context-specific roles with their rigid conception of tribal chieftaincy.

Initial Confusion Among British Officials

The confusion between egalitarian clan leaders and stereotypical “authoritative tribal chiefs” is evident in the writings of colonial administrators and anthropologists of the time. For instance, Sir Philip Mitchell, a key figure in shaping colonial policy, described East African societies as being composed of “tribes,” each united under a single chief (Uganda, 1939). While this description may have partially reflected Buganda’s structure, it bore little resemblance to the realities of Lango or Teso, where no such hierarchy existed. Despite this mismatch, colonial officials proceeded to impose structures based on their flawed assumptions.

Tosh (1978) documents how district officers initially struggled to reconcile their expectations with the actual dynamics they encountered. In Lango, for example, British administrators assumed that the leaders of small clan sections were equivalent to the authoritative tribal chiefs they envisioned. This misunderstanding stemmed from both ignorance and cognitive dissonance—the tension between observed reality and ingrained beliefs. Rather than questioning their assumptions, officials sought to mould local leaders into the roles they had imagined, often appointing individuals as “chiefs” despite their lack of traditional legitimacy.

Cognitive Dissonance and Reinforcement of Misconceptions

Over time, British officials developed strategies to reduce the discomfort caused by cognitive dissonance. According to Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance, individuals experiencing inconsistency between their beliefs and reality will take steps to restore harmony, either by altering their perceptions or adding consonant elements to justify their actions. In the case of Uganda, reflective administrators coped by convincing themselves that appointed chiefs were representative of local communities, even though no institutional mechanisms existed for validating this claim.

For example, Morris (1972) notes that district officers in the 1920s and early 1930s began to regard appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy based on tribal custom. Speaking of this period, Tosh writes: “District Officers—unlike their pre-war predecessors—were beginning to assume that the chiefs were traditional authorities who should be disturbed as little as possible” (1978: 245). This shift in perception allowed officials to rationalise their reliance on appointed chiefs, framing their actions as building upon existing institutions rather than imposing foreign ones.

However, this belief was problematic. As Tosh points out, many appointed chiefs were merely bureaucratic agents tasked with enforcing colonial policies, collecting taxes, and maintaining order. Their powers far exceeded anything traditionally accorded to leaders in societies like Lango or Teso. Peasants subjected to extortionate labour demands and arbitrary exercise of chiefly power were less inclined to view these figures as legitimate representatives of their communities.

The Impact of Misconceptions on Indigenous Societies

The imposition of stereotypical “authoritative tribal chiefs” onto egalitarian societies had significant consequences. In regions like Lango, where leadership roles were historically fluid and contingent upon specific circumstances, the creation of permanent chieftaincies disrupted existing social dynamics. Appointed chiefs, wielding coercive powers granted by the colonial state, became tools of exploitation rather than mediators of communal interests. This transformation sowed seeds of resentment among ordinary peasants, who found themselves at odds with figures they perceived as artificial constructs.

Moreover, the blurring of lines between traditional and colonial authority made it difficult to distinguish genuine indigenous practices from imposed structures. Over time, some appointed chiefs learned to manipulate the system, passing their positions down to their sons and mimicking the principle of hereditary succession. This phenomenon further entrenched the illusion of continuity between precolonial and colonial systems, complicating efforts to reclaim authentic traditions after independence.

Lessons and Legacy

The misconceptions held by British officials highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts. By conflating egalitarian clan leaders with stereotypical “authoritative tribal chiefs,” colonial administrators reshaped Ugandan societies in ways that continue to resonate today. Understanding these dynamics provides valuable insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for equitable governance.

For contemporary policymakers, the lessons are clear. Recognising diversity and fostering inclusive governance requires moving away from rigid hierarchies and embracing participatory approaches that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. Only by acknowledging and addressing historical distortions can we forge a path toward justice and representation in modern-day Africa.

In sum, the initial confusion surrounding tribal leadership underscores both the ingenuity and the limitations of British colonial policy in Uganda. While the imposition of chiefs served immediate administrative goals, it also reshaped social dynamics in ways that continue to influence the nation’s trajectory. By examining these transformations through the lens of scholarly research, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in a colonial setting.

Changing Perceptions Over Time: Tracing the Evolution of British Attitudes, from Viewing Chiefs as Tools of Administration to Seeing Them as Representatives of Indigenous Legitimacy

In the colonial history of Uganda, few phenomena illustrate the complexities of British rule more vividly than the shifting perceptions of African chiefs. Over the course of several decades, British administrators evolved in their understanding of these figures—from viewing them purely as bureaucratic tools designed to serve colonial interests, to regarding them as embodiments of indigenous legitimacy and tradition. This transformation was neither linear nor uniform but rather reflective of broader ideological currents, administrative challenges, and the dynamic interplay between colonial policies and local realities. By tracing this evolution, we gain critical insights into how British attitudes adapted to the Ugandan context and the enduring implications of these changes.

Initial Perceptions: Chiefs as Tools of Administration

When British colonial rule was first established in Uganda, administrators approached governance with a utilitarian mindset. Chiefs were seen primarily as instruments of administration—appointed or co-opted individuals tasked with enforcing colonial laws, collecting taxes, and maintaining order among local populations. This perspective was rooted in the principles of indirect rule, which sought to govern vast territories efficiently by leveraging existing structures (or creating them where they did not exist).

In regions like Buganda, where hierarchical systems already existed, the imposition of chiefly authority aligned relatively smoothly with British expectations. However, in acephalous societies such as Lango and Teso, where leadership roles were fluid and non-institutionalised, the creation of permanent chieftaincies represented a radical departure from precolonial norms. As Tosh (1978) notes, early British officials often conflated egalitarian clan leaders with their stereotype of authoritative tribal chiefs, leading to significant dissonance between observed reality and ingrained assumptions.

During this pioneering phase, district officers viewed their appointed chiefs as junior officials within the colonial hierarchy, devoid of any intrinsic legitimacy. The emphasis was on functionality rather than representation. Chiefs were expected to act as intermediaries between the colonial state and the governed populace, ensuring compliance with imperial edicts. Their powers far exceeded anything traditionally accorded to leaders in many Ugandan societies, making them tools of exploitation rather than mediators of communal interests.

Growing Realism: Searching for Local Men of Importance

As time passed, British administrators began to adopt a more pragmatic approach, recognising that the initial imposition of artificial structures had limitations. Experience revealed the need to identify “local men of importance” who could fill offices within the imported framework modelled on Buganda’s centralised system. These individuals were then educated in the performance of their new roles, blending colonial objectives with elements of local custom.

This shift marked an important step toward greater realism. For instance, in Teso, where precolonial political systems varied significantly across regions, British officials sought to consolidate leadership by appointing local men as chiefs under Ganda territorial administrators. While these appointments remained foreign constructs, they incorporated some degree of local influence, albeit superficially. Similarly, in Lango, efforts were made to integrate clan elders and ritual leaders into the colonial apparatus, though the results were mixed at best.

Despite these adjustments, the underlying premise remained unchanged: chiefs were still viewed as extensions of colonial authority, serving the needs of the empire rather than those of their communities. However, this period laid the groundwork for further transformations in British attitudes.

Emerging Belief in Indigenous Legitimacy

By the 1920s and early 1930s, a notable shift occurred in how British officials perceived their appointed chiefs. District officers began to regard these figures not merely as bureaucratic agents but as representatives of indigenous legitimacy. Speaking of this period, Tosh observes: “District Officers—unlike their pre-war predecessors—were beginning to assume that the chiefs were traditional authorities who should be disturbed as little as possible” (1978: 245).

This belief allowed officials to rationalise granting their appointees considerable latitude, even though these individuals lacked genuine traditional status. In regions like Lango and Teso, where no hereditary leadership existed before colonial intervention, the assumption of indigenous legitimacy was particularly problematic. Yet, it persisted because it aligned with conservative ideology, which celebrated hierarchy and organic social order. To British administrators steeped in this worldview, the idea of an acephalous society was inconceivable—a contradiction that challenged their understanding of how human communities should function.

The cognitive dissonance experienced by officials played a crucial role in this transformation. According to Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance, individuals experiencing inconsistency between cognitive elements will take steps to reduce tension, either by altering their perceptions or adding consonant elements to justify their actions. In the case of Uganda, reflective administrators coped by convincing themselves that the British-imposed chiefly structure was eventually accepted as part of local tradition. Morris (1972), for example, argues that in certain parts of the country, this belief was soundly based, particularly in Busoga, where the Soga people viewed the apparatus of client chiefs and local government as a legitimate continuation of precolonial states (cited in Tosh, 1978).

Factors Contributing to the Change

Several factors contributed to the evolution of British attitudes over time:

- Administrative Convenience : Granting chiefs greater autonomy simplified governance, allowing district commissioners to focus on broader administrative tasks while relying on local intermediaries for day-to-day operations.

- Cultural Assimilation : Some appointed chiefs skilfully manipulated the system to consolidate their positions, passing them down to their sons and mimicking the principle of hereditary succession. This blurring of lines between colonial creations and traditional institutions reinforced the illusion of continuity.

- Conservative Ideology : The conservative mode of thought, prevalent among British administrators, predisposed them to view all African societies through the lens of hierarchy and tradition. This ideological framework shaped their interpretations of local realities, often leading them to impose structures that mirrored their own cultural biases.

- Reflection and Scholarship : A minority of reflective officials engaged in scholarly inquiry, reading widely and conducting their own investigations into African custom and history. While unable to ignore the artificial nature of many colonial creations, these men added consonant elements to their beliefs, arguing that appointed chiefs were representative of local communities, at least in terms of policy implementation.

Legacy and Implications

The evolving perception of chiefs—from tools of administration to representatives of indigenous legitimacy—left a lasting legacy on Ugandan society. Post-independence governments inherited administrative structures built around these hybrid figures, complicating efforts to forge inclusive governance models. The contradictions inherent in the system highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts.

For contemporary policymakers, the lessons are clear. Recognising diversity and fostering equitable governance requires moving away from rigid hierarchies and embracing participatory approaches that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. Understanding the dynamics of changing perceptions provides valuable insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for justice and representation in modern-day Africa.

In sum, the evolution of British attitudes toward African chiefs underscores both the ingenuity and the limitations of colonial policy in Uganda. While the imposition of chiefs served immediate administrative goals, it also reshaped social dynamics in ways that continue to influence the nation’s trajectory. By examining these transformations through the lens of scholarly research, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in a colonial setting.

Teso Case Study: A Detailed Account of Teso District, Where Conquest by Ganda General Kakunguru Led to Unique Patterns of Governance

The history of Teso District in colonial Uganda offers a compelling case study of how external conquest and administrative imposition shaped local governance structures. Unlike regions such as Buganda, where British administrators encountered a centralised monarchy that could be co-opted into the colonial framework, Teso presented a starkly different social and political landscape. Here, the absence of institutionalised chieftaincies and the fluidity of precolonial leadership created challenges for colonial rule. The district’s unique patterns of governance were further shaped by its initial conquest by General Kakunguru, a Baganda military leader acting on behalf of the British, which introduced an additional layer of complexity to the colonial administration.

Precolonial Political Systems in Teso

Before the arrival of colonial forces, Teso society operated without hereditary or centralised leadership structures. Vincent (1982) highlights how variations in ecological and demographic factors influenced the region’s political systems. In some areas, war leaders emerged temporarily during times of need—such as conflict or crises—but their authority was contingent upon success and dissolved once the situation resolved. Clan elders and ritual leaders exercised influence over specific domains, such as spiritual matters or dispute resolution, while age-set systems provided a basis for military organisation in certain parts of the region.

The 19th century had already seen significant changes in these systems. For instance, areas closer to caravan routes used by traders experienced a tendency toward consolidation of leadership, while northern regions exhibited a decrease in political scale. This diversity made it difficult for colonial administrators to impose a uniform system of governance, as no single model existed across the region.

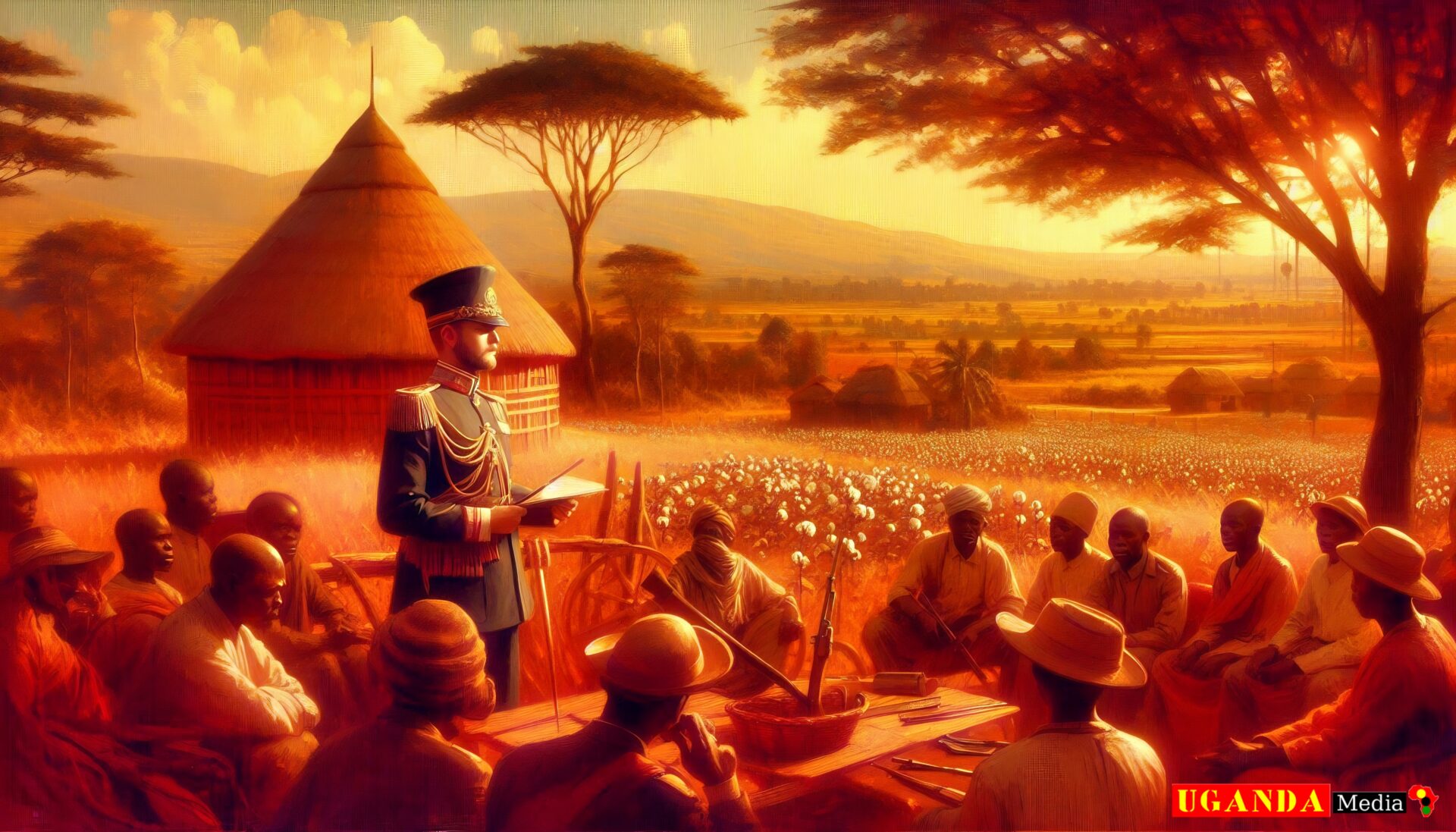

Conquest by Kakunguru and Initial Administration

Teso’s incorporation into the British protectorate was achieved through military conquest led by General Kakunguru, a prominent figure in the service of the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC). Kakunguru’s forces subdued much of what became Eastern Province, including Teso, and established a hybrid administrative structure. Under this arrangement, Ganda territorial administrators were appointed to oversee local governance, while local men were installed as “chiefs” under them.

This dual system reflected both the practical exigencies of colonial rule and the limitations of precolonial institutions. The Ganda administrators brought with them elements of Buganda’s hierarchical model, which they sought to replicate in Teso. However, the imposition of these structures clashed with the acephalous nature of Teso society, where leadership roles were traditionally fluid and non-institutionalised. As Tosh (1978) notes, the artificial creation of chiefly positions radically transformed both the qualitative and quantitative dimensions of authority in the region.

Hybrid Governance Structures

The governance structures established in Teso under Kakunguru’s regime represented a blend of imported and indigenous elements. On one hand, the appointment of local men as chiefs attempted to legitimise colonial authority by incorporating familiar faces into the administrative hierarchy. On the other hand, the overarching presence of Ganda administrators ensured that ultimate control remained in the hands of the colonial state.

This hybrid system created tensions between the various layers of authority. Local appointees often found themselves caught between fulfilling British expectations and maintaining credibility among their own communities. Meanwhile, Ganda administrators, who viewed themselves as superior intermediaries, sometimes clashed with local leaders over jurisdiction and resource allocation. These dynamics underscored the fragility of the imposed system and highlighted the difficulties of reconciling colonial objectives with local realities.

British Perceptions and Evolving Policies

Over time, British perceptions of Teso’s governance evolved in response to administrative challenges and ideological shifts. Initially, colonial officials conflated the egalitarian leaders of small clan sections with their stereotype of authoritative tribal chiefs. This misconception stemmed from a broader conservative ideology that assumed all African societies were inherently hierarchical (Mitchell, 1939). However, experience soon revealed the inadequacy of this assumption. By the 1920s and early 1930s, district officers began to regard their appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy based on tribal custom—a belief that allowed them to grant greater latitude to these figures despite their artificial origins (Tosh, 1978: 245).

This shift in perception was partly driven by cognitive dissonance among administrators. As Tosh argues, reflective officials coped with the disjunction between observed reality and ingrained beliefs by adding consonant elements to justify their actions. For example, they convinced themselves that the British-imposed chiefly structure was eventually accepted as part of local tradition, even though evidence suggested otherwise in numerous instances (Tosh, 1978: 247). In Teso, where no hereditary leadership existed prior to colonial intervention, this belief was particularly problematic. Nevertheless, it persisted because it aligned with conservative ideology, which celebrated hierarchy and organic social order.

precolonial Teso lacked the rigid hierarchies assumed by colonial administrators, the imposition of chiefly authority fundamentally altered existing power dynamics. Appointed chiefs wielded powers far beyond those traditionally accorded to leaders in Teso society, often using their positions to extract resources and labour from peasants under coercive conditions. This transformation sowed seeds of resentment among ordinary peasants, who found themselves at odds with figures they perceived as artificial constructs.

Legacy and Implications

The legacy of Teso’s unique patterns of governance extends far beyond the colonial period. Post-independence governments inherited administrative structures built around hybrid figures, complicating efforts to forge inclusive governance models. The contradictions inherent in the system highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts.

For contemporary policymakers, the lessons are clear. Recognising diversity and fostering equitable governance requires moving away from rigid hierarchies and embracing participatory approaches that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. Understanding the dynamics of governance in Teso provides valuable insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for justice and representation in modern-day Africa.

In sum, the conquest of Teso by General Kakunguru and the subsequent imposition of hybrid governance structures illustrate both the ingenuity and the limitations of British colonial policy in Uganda. While the system served immediate administrative goals, it also reshaped social dynamics in ways that continue to influence the nation’s trajectory. By examining these transformations through the lens of scholarly research, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in a colonial setting.

Ecological Influences on Political Systems: Discussing How Ecological and Demographic Factors Shaped Precolonial Political Systems Across Regions Like Teso

The precolonial political systems of Uganda were not static or uniform but rather deeply influenced by ecological and demographic factors that varied across regions. In areas like Teso, these influences played a pivotal role in shaping the structure, scale, and dynamics of governance. By examining how environmental conditions and population patterns interacted with social organisation, we gain critical insights into the diversity of Ugandan societies before colonial intervention—and why attempts to impose uniform administrative structures often failed.

Ecological Context and Resource Availability

Ecology—the interplay between geography, climate, and natural resources—was a fundamental determinant of political organisation in precolonial Uganda. Regions like Teso, situated in the eastern part of the country, exhibited marked ecological diversity, which directly impacted settlement patterns, economic activities, and leadership structures.

For instance, Vincent (1982) highlights how variations in ecological conditions influenced the development of political systems across Teso. Areas closer to caravan routes used by traders, such as parts of southern Teso, experienced greater interaction with external influences, fostering a tendency toward consolidation of leadership. These zones benefited from access to trade networks, which encouraged larger groupings under more centralised authority figures who could regulate commerce and mediate disputes. In contrast, northern Teso, characterised by less fertile soils and lower population densities, saw a decrease in political scale during the 19th century. Leadership here was fragmented, emerging only temporarily during times of need, such as conflict or crises.

This ecological variability underscores the adaptability of human societies to their environments. Where resources were abundant and accessible, political systems tended to be more hierarchical and enduring. Conversely, in resource-scarce or marginal areas, leadership roles remained fluid and context-specific, reflecting the challenges of sustaining large-scale coordination.

Demographic Factors and Social Organisation

Demographics—the size, density, and distribution of populations—also shaped precolonial political systems in significant ways. Population growth or decline influenced the complexity of social organisation and the emergence of leadership roles. For example, densely populated areas often required more structured forms of governance to manage shared resources, resolve conflicts, and maintain order. Sparse populations, on the other hand, typically relied on kinship ties and clan-based systems for social cohesion.

In Teso, demographic trends mirrored ecological conditions. Southern Teso, with its relatively fertile land and proximity to trade routes, supported higher population densities, facilitating the rise of war leaders who occasionally led larger groupings. However, these leaders derived their authority solely from success in specific endeavours; their influence dissolved once the immediate need passed. Northern Teso, conversely, experienced a depopulation trend during the turbulent 19th century, likely due to environmental stressors and increased raiding. This demographic contraction contributed to the fragmentation of political authority, leaving behind small, autonomous units governed by clan elders and ritual leaders.

Warfare, Migration, and Political Scale

The ecological and demographic landscape of Teso also determined the frequency and intensity of warfare, which in turn influenced political systems. In regions where competition over scarce resources was fierce, militarisation became a key factor in shaping leadership structures. War leaders emerged as temporary figures of authority, rallying groups for defence or expansion. Age-set systems provided a basis for military organisation in some areas, enabling collective action against external threats.

However, the impact of warfare on the political scale varied significantly. In southern Teso, the consolidation of leadership may have been driven by the need to defend against incursions or participate in regional trade. Meanwhile, in northern Teso, repeated raids and instability likely undermined efforts to establish stable hierarchies, reinforcing acephalous (leaderless) arrangements. This divergence illustrates how similar pressures could produce vastly different outcomes depending on local contexts.

Contrasting Patterns Across Uganda

The case of Teso is emblematic of broader trends observed across Uganda. Regions with favourable ecological conditions, such as Buganda, Bunyoro, and Ankole, developed centralised monarchies capable of mobilising labour, resources, and armies. These kingdoms thrived on fertile soils, navigable waterways, and strategic locations that facilitated agriculture and trade. By contrast, acephalous societies like those found in Lango, Acholi, and parts of Teso operated within less hospitable environments, relying on egalitarian principles and fluid leadership roles to navigate uncertainty.

These differences posed significant challenges for British administrators attempting to implement indirect rule. The imposition of hierarchical chieftaincies onto acephalous societies was particularly problematic, as it clashed with existing norms and expectations. Tosh (1978) documents how district officers initially struggled to reconcile their assumptions about authoritative tribal chiefs with the realities they encountered in regions like Lango and Teso. Over time, however, officials came to view their appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy—a belief rooted more in ideological convenience than historical accuracy.

Legacy of Ecological Adaptation

Understanding the ecological and demographic foundations of precolonial political systems provides valuable lessons for contemporary governance. Colonial interventions often ignored these nuances, imposing artificial structures that disrupted indigenous practices and exacerbated tensions. Post-independence governments inherited these distortions, complicating efforts to forge inclusive and equitable models of administration.

For policymakers today, recognising the importance of ecological and demographic factors can inform strategies for sustainable development and conflict resolution. Just as precolonial societies adapted to their environments, modern institutions must account for regional diversity and local needs to ensure effective governance.

Conclusion

The relationship between ecology, demography, and political organisation in precolonial Uganda reveals the remarkable adaptability of human societies to their surroundings. In Teso, ecological and demographic factors shaped the evolution of leadership structures, from the temporary war leaders of the south to the fragmented clan-based systems of the north. These patterns highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts and underscore the enduring legacies of colonial rule. By studying these dynamics, we deepen our appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in both historical and contemporary settings.

War Leaders Turned Chiefs: Describing How War Leaders in Some Areas Assumed Temporary Authority, Contrasting with More Stable Hierarchical Structures Elsewhere

In the precolonial political landscape of Uganda, leadership roles were as diverse as the regions themselves. While some areas, such as Buganda, Bunyoro, and Ankole, boasted stable hierarchical structures with enduring monarchies, other regions operated under more fluid systems where authority was contingent upon specific circumstances. Among these fluid systems, war leaders emerged as temporary figures of authority, wielding power only during times of crisis or need. This phenomenon, particularly evident in regions like Teso and parts of Lango, contrasts sharply with the centralised monarchies that dominated southern Uganda. By examining how war leaders assumed authority—and how their roles differed from more stable hierarchical systems—we gain critical insights into the diversity of Ugandan societies and the challenges faced by British colonial administrators in imposing uniform governance structures.

The Nature of War Leadership in Fluid Societies

In regions without institutionalised chieftaincies, such as Teso and parts of Lango, leadership roles were inherently transient and context-specific. War leaders emerged during periods of conflict, raiding, or external threats, rallying groups for collective action. Their authority was not hereditary or permanent but rather dependent on success and the immediate needs of the community. As Vincent (1982) notes, these leaders derived their legitimacy from their ability to protect their people, secure resources, or achieve military victories. Once the crisis passed, their authority dissolved, and society reverted to its usual patterns of clan-based or ritual leadership.

For example, in Teso, war leaders occasionally led relatively large groupings during the turbulent 19th century, particularly in response to increased raiding and instability. However, their leadership remained provisional, emerging only when necessary and dissolving once the threat subsided. Clan elders and ritual leaders continued to exercise influence over spiritual matters and dispute resolution, while age-set systems provided a basis for military organisation in certain areas. These arrangements ensured that no single individual held enduring power, reflecting the acephalous (leaderless) nature of many Ugandan societies.

Contrast with Stable Hierarchical Structures

The fluidity of leadership in regions like Teso and Lango stands in stark contrast to the stable hierarchical structures found in Buganda, Bunyoro, and Ankole. In these kingdoms, leadership was institutionalised, with clear lines of succession and enduring authority vested in monarchs (such as the Kabaka in Buganda). These rulers wielded significant power over centralised administrations, supported by networks of appointed chiefs and councils. Their authority was rooted in tradition, ritual, and history, making them symbols of continuity and communal identity.

The differences between these systems highlight the adaptability of human societies to their environments. Stable hierarchies thrived in regions with abundant resources, fertile soils, and strategic locations that facilitated agriculture, trade, and population growth. In contrast, fluid leadership structures prevailed in resource-scarce or marginal areas, where communities relied on egalitarian principles and kinship ties to navigate uncertainty. These variations posed significant challenges for British administrators attempting to impose uniform administrative structures across Uganda.

British Misinterpretations and Impositions

When British colonial rule was established in Uganda, administrators approached governance with a utilitarian mindset, seeking to leverage existing structures—or create them where they did not exist—to serve imperial interests. However, their assumptions about African leadership were deeply flawed, particularly in regions like Teso and Lango. British officials initially conflated the egalitarian leaders of small clan sections with their stereotype of authoritative tribal chiefs, leading to significant dissonance between observed reality and ingrained beliefs.

In regions where war leaders had assumed temporary authority, the imposition of permanent chieftaincies fundamentally altered existing power dynamics. Appointed chiefs, wielding powers far beyond those traditionally accorded to leaders in these societies, became tools of exploitation rather than mediators of communal interests. This transformation sowed seeds of resentment among ordinary peasants, who found themselves at odds with figures they perceived as artificial constructs.

Case Study: Teso and the Legacy of War Leadership

The case of Teso illustrates the complexities of imposing hierarchical structures onto fluid leadership systems. Precolonial Teso lacked institutionalised chiefs, with authority resting in the hands of clan elders, ritual leaders, and occasional war leaders. The British conquest of Teso, led by General Kakunguru, introduced a hybrid administrative structure that combined Ganda territorial administrators with local men appointed as chiefs. This system clashed with the acephalous nature of Teso society, where leadership roles were traditionally fluid and non-institutionalised.

Over time, certain appointed chiefs skilfully manipulated the system to consolidate their positions, passing them down to their sons and mimicking the principle of hereditary succession. As Tosh (1978) documents, this blurring of lines between colonial creations and traditional institutions reinforced the illusion of continuity. District officers began to regard their appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy based on tribal custom, despite evidence to the contrary. This belief allowed them to grant greater latitude to these figures, even though they lacked genuine indigenous status.

Legacy and Implications

The legacy of war leaders turned chiefs extends far beyond the colonial period. Post-independence governments inherited administrative structures built around hybrid figures, complicating efforts to forge inclusive governance models. The contradictions inherent in the system highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts.

For contemporary policymakers, the lessons are clear. Recognising diversity and fostering equitable governance requires moving away from rigid hierarchies and embracing participatory approaches that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. Understanding the dynamics of war leadership provides valuable insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for justice and representation in modern-day Africa.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of war leaders assuming temporary authority in regions like Teso and Lango underscores the remarkable adaptability of human societies to their environments. While these fluid leadership systems contrast sharply with the stable hierarchies of Buganda and Bunyoro, both reflect the ingenuity and resilience of Ugandan communities. By examining these transformations through the lens of scholarly research, we deepen our appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in both historical and contemporary settings.

Clan Elders and Ritual Leaders: Emphasizing the Roles of Elders and Spiritual Figures in Societies Without Institutionalized Chiefs

In precolonial Uganda, societies without institutionalized chiefs relied heavily on clan elders and ritual leaders to maintain social order, resolve disputes, and guide communal life. These figures played essential roles that were deeply embedded in the fabric of their communities, ensuring cohesion, continuity, and cultural preservation. In regions such as Lango, Teso, and parts of Acholi—where hierarchical leadership structures were absent or fluid—the contributions of clan elders and spiritual leaders became particularly significant. By examining their functions and influence, we gain critical insights into how these societies operated and why British colonial administrators often misunderstood their roles.

The Role of Clan Elders in Social Governance

Clan elders were central to decision-making processes in acephalous (leaderless) societies. Unlike hereditary chiefs in Buganda or Bunyoro, who derived authority from formal titles and enduring positions, clan elders earned respect through age, wisdom, and experience. Their leadership was contextual rather than permanent; they convened councils to deliberate on matters affecting the community, such as land disputes, marriage arrangements, and responses to external threats.

In Lango, for example, elder councils served as forums for collective decision-making. Decisions were reached through consensus, reflecting the egalitarian principles underpinning these societies. The absence of centralized authority meant that power was dispersed among various clans, each governed by its own elders. This system fostered inclusivity but also required constant negotiation and compromise to address inter-clan issues.

Similarly, in Teso, clan elders exercised considerable influence over domestic and communal affairs. While war leaders occasionally emerged during times of crisis, their authority dissolved once the need passed, leaving elder councils to resume governance. As Vincent (1982) notes, variations in ecological and demographic factors influenced the prominence of elder leadership across different parts of Teso. In resource-scarce northern regions, where political scale decreased during the 19th century, elder councils became even more vital in maintaining stability amidst adversity.

Ritual Leaders and Spiritual Authority

Ritual leaders complemented the work of clan elders by addressing spiritual dimensions of communal life. In societies without institutionalized chiefs, these figures mediated between the human and supernatural realms, performing ceremonies, offering sacrifices, and interpreting omens. Their roles extended beyond religious duties to include moral guidance and conflict resolution.

For instance, in Teso, ritual leaders were instrumental in reinforcing social norms and values. They presided over rites of passage, such as initiation ceremonies, which marked transitions from childhood to adulthood. These events not only strengthened individual identity but also reinforced group solidarity. Additionally, ritual leaders often acted as custodians of oral traditions, preserving histories, myths, and customs that defined communal identity.

In Lango, spiritual figures similarly bridged the gap between practical governance and metaphysical concerns. They invoked ancestral spirits to bless harvests, protect warriors, and heal illnesses. Their involvement in dispute resolution added a layer of legitimacy to decisions, as outcomes were believed to align with divine will. This dual role underscored the interconnectedness of secular and sacred spheres in acephalous societies.

British Misinterpretations and Impositions

When British colonial rule was established in Uganda, administrators approached governance with a utilitarian mindset, seeking to impose hierarchical structures modelled on Buganda’s centralized monarchy. However, their assumptions about African leadership were deeply flawed, particularly in societies like Lango and Teso. British officials initially conflated clan elders and ritual leaders with their stereotype of authoritative tribal chiefs, leading to significant dissonance between observed reality and ingrained beliefs.

Tosh (1978) documents how district officers struggled to reconcile their expectations with the realities they encountered. For example, in Lango, British administrators assumed that clan elders held powers akin to those of hereditary chiefs, despite evidence to the contrary. This misconception stemmed from a broader conservative ideology that assumed all African societies were inherently hierarchical (Mitchell, 1939). Over time, however, officials came to regard appointed chiefs as possessing traditional legitimacy—a belief rooted more in ideological convenience than historical accuracy.

This shift had profound implications for clan elders and ritual leaders. The imposition of permanent chieftaincies fundamentally altered existing power dynamics. Appointed chiefs, wielding powers far beyond those traditionally accorded to leaders in these societies, became tools of exploitation rather than mediators of communal interests. This transformation sowed seeds of resentment among ordinary peasants, who found themselves at odds with figures they perceived as artificial constructs.

Legacy and Implications

The legacy of clan elders and ritual leaders extends far beyond the colonial period. Post-independence governments inherited administrative structures built around hybrid figures, complicating efforts to forge inclusive governance models. The contradictions inherent in the system highlight the dangers of imposing foreign models without regard for indigenous contexts.

For contemporary policymakers, the lessons are clear. Recognizing diversity and fostering equitable governance requires moving away from rigid hierarchies and embracing participatory approaches that reflect the needs and traditions of all communities. Understanding the roles of clan elders and ritual leaders provides valuable insights into the enduring legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for justice and representation in modern-day Africa.

Conclusion

Clan elders and ritual leaders were indispensable pillars of governance in precolonial Ugandan societies without institutionalized chiefs. Their roles reflected the adaptability and resilience of human communities to their environments. By examining these transformations through the lens of scholarly research, we deepen our appreciation for the complexities of power, tradition, and change in both historical and contemporary settings.

Conservative Ideology and Colonial Governance: Exploring Conservative Thought Among British Administrators, Focusing on Their Belief in Hierarchy and Organic Social Change

The governance of colonial Uganda was profoundly shaped by the conservative ideology that permeated the worldview of British administrators. Rooted in a belief in hierarchy, tradition, and organic social evolution, this ideological framework informed how officials approached their roles, interpreted African societies, and implemented policies. By examining the principles of conservative thought and their application in the Ugandan context, we gain critical insights into both the successes and failures of colonial governance—and the enduring legacies of these attitudes.

Core Principles of Conservative Thought

Conservative ideology, as embraced by many British administrators, rested on several key tenets that influenced their approach to governance. These principles can be distilled into three central ideas:

- Hierarchy as Natural Order : Conservatives viewed society as inherently hierarchical, with individuals occupying distinct roles based on tradition, custom, and function. This belief extended to their understanding of African societies, where they assumed all communities were structured around authoritative tribal chiefs. Sir Philip Mitchell, a prominent colonial administrator, encapsulated this perspective when he stated that “authorities…with the habit as well as the power to rule” were prerequisites for organized social life (Uganda, 1939: 4). To conservatives, an acephalous (leaderless) society was not merely unusual but a contradiction—a monstrous impossibility.

- Intermediate Groups as Social Pillars : In the conservative tradition, individuals were seen not as isolated entities relating directly to the state but as members of smaller intermediate groups, such as clans, tribes, or estates. These groups provided stability, continuity, and a sense of identity. In the African context, these “intermediate groups” became synonymous with “tribes,” which were assumed to be discrete, enduring units with clear boundaries. This assumption underpinned much of colonial policy, including indirect rule, which sought to govern through supposedly traditional institutions.

- Organic Social Change : Conservatives rejected abrupt or radical transformations, advocating instead for gradual, incremental change rooted in existing structures. They believed that societal progress should occur naturally, like the growth of an organism, rather than being imposed arbitrarily. This emphasis on organic evolution aligned with their preference for building upon perceived traditional institutions, even if those institutions were artificially constructed or misunderstood.

These principles formed the bedrock of conservative thought among British administrators, shaping their interactions with Ugandan societies and influencing the design of colonial governance systems.

Application in Colonial Uganda

The application of conservative ideology in Uganda is evident in the implementation of indirect rule and the imposition of hierarchical structures onto diverse societies. However, the degree to which these principles resonated with local realities varied significantly across regions.

- Buganda: A Model Fit for Conservative Ideals

In Buganda, the centralized monarchy led by the Kabaka offered a near-perfect alignment with conservative ideals. The hierarchical structure, complete with appointed chiefs (batongole ) and clan leaders, mirrored the orderly vision cherished by British administrators. Through the 1900 Buganda Agreement, colonial officials formalized this arrangement, granting Buganda a degree of autonomy while ensuring cooperation with British interests. For conservatives, Buganda represented a harmonious blend of tradition and modernity—a model to be emulated elsewhere in the protectorate. - Lango and Teso: Misapplication of Conservative Principles

In regions like Lango and Teso, where acephalous societies operated without institutionalized chieftaincies, the imposition of hierarchical structures created profound dissonance. Precolonial leadership in these areas was fluid, emerging only temporarily during times of need and dissolving once the situation resolved. Clan elders and ritual leaders exercised influence over specific domains, but their authority was neither permanent nor coercive.Despite these realities, British administrators imposed artificial chieftaincies modelled on the Buganda system. As Tosh (1978) notes, officials initially confused egalitarian clan leaders with their stereotype of authoritative tribal chiefs, leading to significant tensions. Over time, however, administrators came to view their appointees as possessing traditional legitimacy, despite evidence to the contrary. This shift reflected the conservative belief in organic social change; district officers assumed that newly created structures would eventually be accepted as part of local tradition.